Archive

Giveaway: Like One of the Family by Alice Childress

I’m pleased to be offering up my first ever giveaway! Out of appreciation to Beacon Press for their generosity in giving both myself and Amy copies of Like One of the Family (review) in support of our The Real Help Reading Project, I’d like to spread the love by passing on the copy to another lucky person!

I’m pleased to be offering up my first ever giveaway! Out of appreciation to Beacon Press for their generosity in giving both myself and Amy copies of Like One of the Family (review) in support of our The Real Help Reading Project, I’d like to spread the love by passing on the copy to another lucky person!

What You’ll Win: One previously read print copy of Like One of the Family by Alice Childress. (It did ride around in my purse on the T, so we are not talking pristine, here).

How to Enter: Leave a comment with your email address so I can contact the winner for his/her mailing address!

Rules: US ONLY. Sorry, I can’t afford to mail anywhere else. If you have a friend in the States willing to let you use their address, that will work too, though. The mailing address must be in one of the 50 US states or Puerto Rico, however. (If you’re an international address, sign up for the same book being given away on Amy’s blog internationally).

Contest Ends: November 26th! The date of our next The Real Help post ;-)

Enter away! Spread the word! Show your love for black women writers and the real experiences of domestic black workers in the 1950s and 1960s! Thanks!

Book Review: Like One of the Family by Alice Childress (The Real Help Reading Project)

Summary:

Summary:

Originally published as a serial in African-American papers in the 1950s this series of monologue-style short stories are all in the voice of Mildred–a daytime maid for white families in New York City. The monologues are all addressed to her best friend and downstairs neighbor, Marge, who is also a maid. The stories range from encounters with southern relatives of moderately minded employers to picnics threatened by the Ku Klux Klan to more everyday occurrences such as a dance that went bad and missing your boyfriend. Mildred’s spitfire personality comes through clearly throughout each entry.

Review:

With completion of this book, Amy and I are officially halfway through our The Real Help Reading Project! This book is our first piece of fiction to directly foray into the time era and relationships depicted in The Help, whereas the rest have shown the slave culture and racial issues leading up to that time period. I’m glad we got the historical context from our previous reads before tackling this one written during the Civil Rights era by an author who periodically worked as a maid herself.

The introduction by Trudier Harris is not to be missed. She provides excellent biographical details of Alice Childress, who was not only a black writer of fiction, but also wrote and performed in plays. I am very glad I took the time to read the introduction and get some context to the author. Harris points out that in real life some of the things the character Mildred says to her employers would at the very least have gotten her fired, so to a certain extent the situations are a bit of fantasy relief for black domestic workers. Mildred says what they wish they could say. Since we know Childress was a domestic worker herself, this certainly makes sense. I would hazard a guess that at least a few of the stories were real life situations that happened to her reworked so she got to actually say her mind without risking her livelihood. I love the concept of this for the basis of a series of short stories.

More than any other work we’ve read, Like One of the Family demonstrates the complexities of living in a forcibly segregated society. Mildred on the one hand works in close contact with white people and subway signs encourage everyone in New York City to respect everyone else, and yet her personal life is segregated. Mildred frequently points out how she can come into someone else’s home to work, but it wouldn’t be acceptable in society for that person to visit her as a friend or vice versa.

Another issue that Childress demonstrates with skill is how a segregated, racist society causes both black and white people to regard each other with undue suspicion. In one story Mildred’s employer asks her if it’s too hot for a dress Mildred already ironed for her and ponders another one. Mildred assumes that if she agrees with her employer that it’s too hot for the first dress, she’ll have to stay late to iron. Her employer instead of getting angry realizes that Mildred has been mistreated this way before and takes it upon herself to reassure Mildred that she herself is perfectly capable of ironing her own dresses and will not keep Mildred longer than their agreed upon quitting time. Of course, Mildred sometimes is the one who must hold her temper and calm irrational fears. In one particularly moving section she encounters a white maid in their respective employers’ shared washroom. The woman is afraid to touch Mildred, and it takes Mildred holding her temper and carefully explaining that they are more similar than different before the woman realizes how much more she has in common with Mildred than with her white employer. These types of scenes show that the Civil Rights movement required bravery in close, one-on-one settings in addition to the more obvious street demonstrations and sit-ins.

Of course the stories also highlight the active attempts at exploitation domestics often encountered. Mildred herself won’t put up for it, but Childress manages to also make it evident that some people might have to simply to get by. An example of this sort of exploitation is the woman who upon interviewing Mildred informs her that she will pay her the second and fourth week of every month for two weeks, regardless of whether that month had five weeks in it or not. What hits home reading these serials all at once that perhaps wouldn’t otherwise is how frequent such a slight was in a domestic’s life during this time period. Mildred does not just have one story like this. She has many.

Of course sometimes reading Mildred’s life all at once instead of periodically as it was intended was a bit desensitizing. Although Mildred had every right to be upset in each situation related, I found myself noticing more and more that Mildred was simply a character for Childress to espouse her views upon the world with. I quickly checked myself from getting bugged by that, though. Of course Childress had every right to be upset and did not originally intend this to be a book of Mildred’s life. Mildred was a vehicle through which to discuss current issues highly relevant to the readers of the paper. It is important in reading historic work to always keep context in mind.

Taking the stories as a whole, I believe they show what must have been one of the prime frustrations for those who cared about Civil Rights during that era, whether black or white. Mildred puts it perfectly:

I’m not upset about what anybody said or did but I’m hoppin’ mad about what they didn’t say or do either! (page 167)

Passivity in changing the system is nearly as bad as actively working to keep the system, and Mildred sees that. Of course what Mildred highlights is a key conundrum for the black domestic worker of the time–speak up and risk your job or stay silent at a cost to the overall condition of those stuck in the system? A very tough situation, and I, for one, am glad that many strong men and women of all races took the risk to stand up and change it.

Source: Copies graciously provided to both Amy and myself by the publisher in support of the project (Be sure to sign up for the giveaway. US only and International).

Discussion Questions:

- How do you think domestics decided where to draw the line in what they would and would not put up with in employment in white people’s homes?

- Some of Mildred’s employers seem to be sensitive to the racial and inequality issues and are very kind to Mildred. Be that as it may, do you think it is/was possible to hire a maid for your home and not have a racist mind-set?

- Do you think the employers Childress depicts attempting to exploit Mildred were doing so out of racism, a power-trip, or greediness or some combination or all three?

- Mildred points out multiple times that she feels that the public ads encouraging people to accept each other “in spite of” their differences are still racist. Do you think this is true?

Bloggers’ Alliance of Nonfiction Devotees (BAND): November Discussion: Reading for a Cause

![]() BAND is a monthly discussion group of book bloggers who love nonfiction! If you’d like to join us, check out our tumblr page.

BAND is a monthly discussion group of book bloggers who love nonfiction! If you’d like to join us, check out our tumblr page.

I am super excited to get to host BAND this month! Because, well, who doesn’t love talking about something they love, right?

I firmly believe in knowledge being power. This is how my dad raised me, and I am forever grateful for that. The more knowledge you have the more strongly you can support your cause. This idea was further developed in me when I went to Brandeis University for undergrad. Brandeis is built around the concept of social justice, and in all of our classes we learned that you can change the world one mind at a time.

Even though I’m out of Brandeis now, I’ve done my best to apply this concept to my reading. I seek to constantly attain greater knowledge in areas that matter to me. Pick your cause and read all about it, essentially.

My very first cause was the health and obesity crisis in the US. I was unhealthy. My family was unhealthy. Most of Americans are unhealthy, so I started reading about alternatives to the way I was raised (the SAD–Standard American Diet). I read a wide arrange of information including excerpts from The China Study, The Blood Type Diet, Vegetarianism for Dummies, and many many more from back before my book blogging days that I unfortunately did not keep good track of. I still have a section of my tbr pile about addressing the health crisis in the US. It matters to me. And I hope that even just by seeing me read the book or seeing a blog post about it, it’ll help to start engaging others into changing their lifestyles.

This reading naturally led me into reading about animal rights, which is something I am incredibly passionate about today. I love nonfiction science books about the inner life of animals, the social networks of dolphins and elephants, and the cruelty of factory farms. I wish I could get one of these books in a week, but for right now I’ll settle for as many as possible, haha.

More recently I’ve become interested in the history of racism in the US and how that history impacts social interactions today. This is what spurred me on to ask Amy to do The Real Help Reading Project with me, and I hope that our presence online discussing these books will help to broaden and change some minds.

Maybe it’s a bit idealistic to think one can evoke social justice and change purely through what you read, but it’s something I can’t help but believe in. I guess Brandeis taught me well.

What about you?

Do you read nonfiction to help support a cause(s)?

Leave links to your posts in the comments! (I have issues making link collectors work for me). Thanks!

Bloggers’ Alliance of Nonfiction Devotees (BAND): October Discussion: Favorite Anthologies

BAND is a monthly discussion group of book bloggers who love nonfiction! If you’d like to join us, check out our tumblr page.

This month Ash of English Major’s Junk Food asks us: What are your favorite nonfiction anthologies?

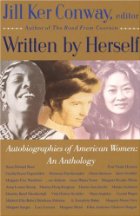

It’s funny; I haven’t read a nonfiction anthology in a while, but I immediately thought of one book that sits proudly on one of my livingroom bookshelves at home that I return to relatively frequently to read bits and pieces from—Written by Herself: Autobiographies of American Women: An Anthology.

Time to toot my own horn a bit here, I was the recipient of the Smith College Book Award in high school, and this was the book they chose to send me. As a young feminist growing up in a rural, traditional area, this book rocked my world. So many strong, intelligent women of all races and ethnicities from many time periods overcoming obstacles to achieve amazing things. Any time I had a rough day in high school or college, I would turn to this book and read a section of it. Um, plus it has a Smith College Book Award bookplate with my name on it, which is just bad-ass. Alas, they were unable to convince me to go to a women’s college. I wanted boys around. ;-) But hopefully the alumni association of Smith will still be pleased to know that this book helped one young girl become a stronger woman.

I’m glad Ash brought up this topic, because it made me think about one of my more unique favorite books, but also realize that it’s been a while since I read a nonfiction anthology. I’ll have to think on a topic that interests me and hunt one down at the library!

Check out the nonfiction books I’ve reviewed and discussed since the August discussion:

- The Last Manchu: The Autobiography of Henry Pu Yi, Last Emperor of China

(review)

- A Stolen Life: A Memoir

(review)

- Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women , Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Present

(review)

- Coming of Age in Mississippi

(review)

- Lean, Long & Strong: The 6-Week Strength-Training, Fat-Burning Program for Women

(review)

Book Review: Coming of Age in Mississippi by Anne Moody (The Real Help Reading Project)

Summary:

Summary:

Anne Moody in her memoir recounts growing up in the Jim Crow law south, as well as her involvement in the Civil Rights movement as a young adult. She was one of the women at the famous Woolworth’s lunch counter sit-in. Here we get to see her first-hand thoughts and memories of the struggle growing up surrounded by institutionalized racism, as well as the difficulties in fighting it.

Discussion:

This project I am co-hosting with Amy truly seems to be flying by! We are already on our fourth read. I was excited that it was my turn to host the discussion, because memoirs are one of my favorite genres (as my followers know). Plus this is a memoir set just before and during the Civil Rights era, which is a time period I must say I don’t know as much about as I should. History classes in the US have a tendency to run out of time in the semester right around the end of WWII.

Throughout the book there is personal, anecdotal evidence of the statistics we read about in Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow. The harsh life as sharecroppers produces anxiety and stress in the family structure. Anne is left alone all day with an uncle who is only eight years old to watch her and who treats her badly because he resents being stuck with this responsibility. Similarly, early in her life, Anne’s father and mother divorce. The strain on the family of poverty is abundantly clear.

Similarly what we read about black women taking nowhere near enough time off of work to recover after pregnancy and birth is evident in Anne’s observations of her own mother:

She didn’t stop workin until a week before the baby was born, and she was out of work only three weeks. She went right back to the cafe. (page 26)

Although Anne’s mother tried to stay out of serving in white homes as a maid, before long she ended up taking on that kind of work. She and her children would generally live in a two-room shanty out back. At first Anne didn’t notice the difference in privilege, until her mother brought home food for her children:

Sometimes Mama would bring us the white family’s leftovers. It was the best food I had ever eaten. That was when I discovered that white folks ate different from us. (page 29)

Anne was clearly an intelligent child and picked up on the subtle situations going on around her. Early on she remembers wondering about race and what makes someone white versus black, when there were some “high yellow” black people she knew who could easily pass for white.

Now I was more confused than before. If it wasn’t the straight hair and the white skin that made you white, then what was it? (page 35)

In fact, this issue of levels of color in black communities impacted Anne’s early life a great deal. Her mother’s second significant relationship was with a man from a “high yellow” family who didn’t want him with her because she was “too dark.” Anne’s mother put up with Raymond trying to decide between her and another “high yellow” woman that his family did approve of for years. Later when he does choose her, she must put up with the snobbery of his family who refused to even speak to her. Anne cannot understand how black people can be so cruel to each other when the white people in Mississippi are cruel to them all. It is evident that the racism and oppression of the South caused those oppressed to seek out others to oppress, and the easiest way to do so was to be prejudiced against those with a darker skin tone. Anne is right that it’s sad and confusing, but it also seems to be a natural result of such an oppressive system. It’s like we learned from The Book of Night Women: misery begets misery.

Before she is even in middle school, Anne has her first job working for a white woman. She sweeps her porches in exchange for milk and a quarter. This is when she starts contributing to the family economy. It’s interesting how Anne never expresses any resentment about needing to contribute to keeping the family going at a young age. She does not view it as her parents’ fault. It is just the way it is, and she’ll do what it takes to help her family.

This is the part of the book where we truly see through the eyes of “the help.” There are families that Anne works for her treat her like an equal, have her eat dinner with them, and encourage her to go to college. Then there is the family that is an active member of “the guild” (aka the KKK) where Anne is constantly in terror that they are going to try to frame her for a false wrong-doing. Anne shows many signs of constant stress during this time, both in her body (headaches and losing weight) and in her mind (feeling trapped). Being stuck working for someone who you know is going around organizing the murder of people of your own skin tone purely for their skin tone must have been horribly traumatizing.

It is in high school when the activity of the KKK in her hometown ramps up that Anne starts to develop her fighting spirit that will carry her out of white people’s homes and into the Civil Rights movement. She is angry and fed up with the system, with white people, but with black people too.

But I also hated Negroes. I hated them for not standing up and doing something about the murders. In fact, I think I had a stronger resentment toward Negroes for letting the whites kill them than toward the whites. Anyway, it was at this stage in my life that I began to look upon Negro men as cowards. (page 136)

Anne’s passion for doing what is right in the face of terrible danger and pain is remarkable and admirable. She would rather die fighting the system than live under the system. She does not seem to realize it, but this is an unusual level of strength and courage. It takes people like her to make change happen. People like her become the leaders that get people to act in spite of their fear. I understand her frustration, but her lack of understanding of other black people’s viewpoints can be a bit frustrating at times.

Her passion though does lead her to one of the historic black colleges, eventually, Tougaloo College. Tougaloo was at the center of a lot of the Civil Rights movement in the south, and I found this part of the book totally fascinating. It is here that Anne makes her first white friend, a fellow Civil Rights activist. It is here that her famous sit-in at Woolworth’s is organized.

But something happened to me as I got more and more involved in the Movement. It no longer seemed important to prove anything. I had found something outside myself that gave meaning to my life. (page 288)

Anne used her jobs in white people’s homes to get herself to college where she joined in the Civil Rights movement. It is a truly inspirational tale. One can’t help but wonder if the KKK household she worked in became aware of her significant achievements. The woman who once washed their dishes and ironed their clothes entered into history books. How anyone can find kitschy stories like The Help inspirational when there are real ones like Anne Moody’s is beyond me.

I was a bit surprised at the semi-dark ending, so I did a bit of googling and discovered that this book was first published in 1968, far before the drastic improvement in race relations in the United States. Moody at the time had no idea how things were going to turn out. It’s understandable she was feeling a bit down-trodden and wondering if anything good would ever happen.

I also learned through googling that this memoir ends before her involvement in the Black Power movement. There are rumblings that she will join with them, though, because she starts stating that peaceful protest will get them nowhere when they are constantly met with violence. I wish there was a follow-up memoir, but there is not, and Anne Moody has refused all media interview requests ever since the publication of this one. I suppose I will simply have to read one of the many famous Black Power books to satisfy my curiosity.

Source: Library

Length: 424 pages – average but on the longer side

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Discussion Questions:

- How do you think poverty and racism impacted Anne’s mother’s two significant relationships with men?

- Do you think those working in KKK households were at a greater physical risk than those working in regular white households?

- Anne’s employer has her tutor her son in Algebra, because he is failing. This would suggest that on some level the woman realized that black people are not inferior to white people. Why do you think she was than so insistent on the dominance of white people and a member of the KKK?

- What are your thoughts on the various southern whites in Anne’s life who actively helped her and protested and/or fought racism? What do you think made them act against a system that they were raised in when others like them were defending it?

- Anne ends the book waffling between peaceful protests and violent movement. Which do you think ultimately would lead to a better end result?

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

Book Review: The Book of Night Women by Marlon James (The Real Help Reading Project)

Summary:

Summary:

This is the story of Lilith. A mulatto with green eyes born on a plantation in Jamaica to a mama who was raped at 14 by the overseer as punishment to her brother. Raised by a whore and a crazy man, all Lilith has ever wanted was to improve her status on the plantation. And maybe to understand why her green eyes seem to freak out slave and master alike. Assigned to be a house slave, Lilith finds herself in direct contact with the most powerful slave on the plantation–Homer, who is in charge of the household. Homer brings her into a secret meeting of the night women in a cave on the grounds and attempts to bring Lilith into a rebellion plot, insisting upon the darkness innate in Lilith’s soul. But Lilith isn’t really sure what exactly will get her what she truly wants–to feel safe and be with the man she cares for.

Discussion:

This is the third book and second fictional work for The Real Help reading project I’m co-hosting with Amy, and it totally blew me away. A reading experience like this is what makes reading projects/challenges such a pleasure to participate in. I never would have picked up this book off the shelf by myself, but having it on the list for the project had me seek it out and determined to read it within a set length of time. Reading the blurb, there’s no way I would imagine identifying with the protagonist so strongly, but I did, and that’s what made for such a powerful experience for me. The more I read literature set in a variety of times and places, the more I see what we as people have in common, instead of our differences.

There is so much subtle commentary within this book to ponder that I’m finding it difficult to unpack and lay out for you all. Part of me wants to just say, “Go read this book. Just trust me on this one,” but then I wouldn’t be doing my job as a book blogger, would I?

Depicted much more clearly here than in any of our reads so far is how detrimental a society based upon racism is for all involved. There is not a single happy story contained here. Everyone’s lives are ruined from the master all the way down to the smallest slave girl. It is a circle of misery begetting misery begetting misery.

Homer was the mistress’ personal slave and many of the evil things that happen to her was because the mistress was so miserable that she make it her mission to make everybody round her miserable as well. (page 415)

Nobody is happy. Everyone lives in misery and fear. The whites are afraid of a black revolt. The blacks are afraid of being whipped or hung. Everyone is afraid of Obeah (an evil witchcraft similar to voodoo). People start to lash out at each other in an attempt to better themselves. For instance, the Johnny-jumpers are male slaves who are pseudo-overseers given power over the other slaves to beat them. It is simply a system exploiting everyone and for what? From the book it appears to be to maintain Britain’s position of power in the world. The system is evil, and it does not simply beget misery, but despair as well. It brings out the worst in everyone.

A strong theme in this book is that of race being a construct rather than an innate true difference in people. Since Lilith is bi-racial, she has trouble simply aligning herself with one side or the other. Although at first she hates white people, she comes to deeply care for a white man. She comes to see people as individuals and not their race, but alas that thought process is far too advanced for the time she is living in, and she senses this.

She not black, she mulatto. Mulatto, mulatto, mulatto. Maybe she be family to both and to hurt white man just as bad as hurting black man…..Maybe if she start to think that she not black or white, then she won’t have to care about neither man’s affairs. Maybe if she don’t care what other people think she be and start think about what she think she be, maybe she can rise over backra and nigger business, since neither ever mean her any good. Since the blood that run through her both black and white, maybe she be her own thing. But what thing she be? (page 277-8)

It’s impossible not to have your heart break for Lilith, a woman whose whole life revolves around race when all she ever wants is to feel happy and safe, an impossible dream represented for her by a picture from a child’s book that her foster slave father let her take from him. The picture is of a sleeping princess with a prince near her, and Lilith’s obsession with this image follows her throughout her life, until she finally tells herself:

She not no fool, Lilith tell herself. She not a sleeping princess and Robert Quinn is not no king or prince. He just a man with broad shoulders and black hair who call her lovey and she like that more than her own name. She don’t want the man to deliver her, she just want to climb in the bed and feel he wrap himself around her. (page 335)

I found myself wishing I could scoop Lilith and Robert up and place them on an island where they could just be together and raise their mixed race babies and just be happy, but that’s not what happened then, and that’s the dream we must keep fighting for, isn’t it? A world where people can just love each other and be happy and not be forced into misery for economic gain of a person or a business or a nation.

I know it sounds like wishful thinking, but that’s really what I got out of this book. If we don’t want to live in a world that dark, we must embrace love in all its forms. Love begets love, but hate begets hate. Don’t like corporate greed or nationalism overtake your capacity to see the humanity in everyone–the capability for powerful good or powerful evil present in us all. Perhaps this is a bit off-topic for The Real Help Reading Project, but that is the old passion from a youthful me in undergraduate classes that this book reignited, and that is what makes me want everyone to read it.

Source: Public Library

Buy It (See all Literary Books)

Please head over to Amy’s post to discuss this book!

Book Review: Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow by Jacqueline Jones (The Real Help Reading Project)

Summary:

Summary:

Professor Jacqueline Jones presents the extensively researched history of the dual working worlds of black American women–at home and in the workforce–from slavery to present. She highlights the ways in which the unique cultural history of slavery as well as being subject to both sexism and racism have impacted black American women’s lives.

Discussion:

This is the second book for the Real Help reading project I’m co-hosting with Amy. I specifically requested that she host the discussion for this book for a special reason. Jacqueline Jones was my professor for one of my classes required for my history major at Brandeis University (she now teaches at University of Texas), and suffice to say, she and I did not get along very well. I was concerned that this history might make it difficult for me to discuss this book, so I asked Amy to host. She obliged. I am going to do my best to discuss this book without bias, but my personal experiences with Jackie Jones (as the Brandeisians called her) definitely gave me my own perspective in reading the book.

I was completely engrossed in the slavery and Jim Crow sections of the book. They taught me a lot I was previously unaware of, as I always kind of avoided the Civil War in my American history classes. (I focused on colonization, Revolutionary War, westward expansion, and WWII). For instance, it was interesting to see how the matriarchy slave owners forced upon slaves affected and impacted black culture even to this day. It was also the first time I saw sharecropping explained and spelled out. It is easy to see how black women, particularly ones widowed or single mothers, would choose to move to a city and become domestic help to escape the back-breaking work of share-cropping.

The book also demonstrates how black American culture has come to depend upon the iconic image of the strong black woman to help them through horrible racism and working conditions. Yet, by the end of the book, we can see that this means a lack of support for black women that is reflected in long-term illnesses and mental illness. Although black women are to be respected and lauded for their role in helping their communities, it is time that less is laid upon them. One obvious thing? Less time spent serving whites.

Since this was read largely to combat The Help, which takes place specifically in a domestic environment during the Civil Rights movement, I want to take a moment to discuss what I learned about that specific era in this book, because the book as a whole obviously covers a very large period of time. The book clearly demonstrates that the Civil Rights movement was BLACK women fighting for BLACK people and sympathetic whites came down from the north to help with things like voter registration, and they were then housed by BLACK women who would literally sit on their porch with a gun to protect the workers. This is in stark contrast to the image laid out in The Help where a WHITE woman comes and convinces the black workers to talk to her for their rights.

Additionally, the book repeatedly demonstrates how black women constantly throughout American history have sought to get out of white homes for any other kind of labor (except in the case of sharecropping). The role of domestic simply rings too close to slavery, and can you blame them? It certainly is apparent that many, if not the majority, of white employers sought to use black domestics as as close an approximation to slave labor as possible. One issue I don’t think the book addressed well enough is that any situation where one is working as a servant in another person’s home serves to antagonize relationships between the two groups. There is no friendliness there. One person is doing a menial chore in the home of another that the other is wealthy enough to not have to do. How could that possibly bring about anything but negative feelings?

Now, ok, here’s my criticism of the book. I feel that in Prof Jones’ passion for the plight of minorities in the US, she can sometimes over-compensate the opposite direction. By that I mean, she sometimes presents minorities as super-human or at no fault for their own actions or she’ll ignore negatives entirely. For instance, we only got two paragraphs out of 480 pages on black women working in prostitution. Personally, I wanted to know more about this, as it is a type of work black women have engaged in (as have every color/race of women ever), and I wanted to know the specific roles sexism, racism, and a hostile culture played in that for them. Specifically, I was interested about how the idea of lighter colored black women being more desirable to white men that we saw in the first book of our challenge might have carried over to prostitution in the 1920s and 1930s. But Jones doesn’t talk about this, and from my own personal experience with her, I speculate this is partly a blinders on her eyes issue.

Similarly, one thing that really irritated me was every time Jones tells a story of a woman working herself to the bone trying to provide for her children only to have her husband abandon her, Jones excuses the man by saying….”Well…..racism,” and moves on. Certainly, I am sure that some of these men were simply stressed out and thus abandoned their families, but I’m also certain that some of them were just assholes and would have done so in a completely non-racist society. To wit, I believe Jones falls too hardly on the nurture side of nature/nurture, when psychiatry has repeatedly demonstrated that it actually is a combination of the two that determines an individual’s behavior. By this I mean, I am certain that a non-racist society would lead to a larger percentage of happy, healthy families, but it by no means would wipe out all questionable behavior by all members of that race. To suggest that all members of a race would be “good” minus racism is just as racist as to suggest that all members of a race are “bad.”

That said, while I enjoyed the earlier portions of the book, as well as the sections on domestic labor in the 1950s and 1960s, I do think the book tries to tackle a bit too much in one entry. The sweep is almost overwhelming at times when reading it. I’d recommend getting a print copy so you can skim for the chapters of most interest to you or so that you can read various sections as questions arise.

Source: Amazon

Please head over to Amy’s post to discuss this book!

Reading Project: The Real Help–Helping Put “The Help” in Historical Context (Co-hosted With Amy of Amy Reads)

What’s a Reading Project?

I am really excited to be doing my first social justice themed reading project, which is different from a reading challenge. A reading challenge challenges you to broaden your reading horizons. A reading project takes a topic that matters to you (or that should matter to you) and creates a reading list about that topic by people who know to help you learn about it, as well as drive discussion on such an important topic. Now, allow me to explain the genesis of and reasons behind my first reading project.

What Led to the Project

I’ve grown to become good friends with Amy of Amy Reads over the past year, and when Kathryn Stockett’s The Help blew up in literary circles then became a movie, well, both of our ires got up. We discussed back and forth the issues via gchat, tumblr, and twitter, sending articles and mini-rants to each other and just generally being peeved that so much of the population got swept up into something so offensive to both black and white women in 2011 for goodness sake.

Let me explain to you in my own words my problem with The Help. Stockett is a white woman who grew up in the south with black maids. She claims that when her maid died she felt regret at never having gotten to know her as a real person, so she decided to write this fiction book about black maids in her home state in the 1960s. Right away, I was offended that her instinct was to write a fictional account instead of, oh I dunno, maybe making an effort to fight racism by befriending black people?

For those who don’t know, The Help is about a college educated white woman who comes home and interviews the black maids in her town and publishes their stories. I cannot really wrap my mind around the thought that Stockett thought of doing a project like this, but instead of being an editor of a collection of memoirs and real-life scenarios by black domestic workers she chose to fictionalize the whole process.

This leads me to one of my largest points. The Help is Stockett living in a fantasy land version of history. One of the first things you learn as a history major is to NOT romanticize the past. You have to get up close and personal with how ugly it truly was. Shows like Leave It To Beaver completely leave out real issues like racism, classism, sexism, etc… This is what Stockett is repeating. She regrets her relationship with her own black maid, so she writes a truly mary-sue style book wherein a college educated white woman gets to know the black female domestic workers and comes to their aid. This isn’t reality. This isn’t a harmless feel-good book/movie. It’s Stockett’s fantasy method of dealing with the racism she grew up with. Why not instead have written a book about a white woman who goes to college in the north and comes to regret the racism she was raised with? Who confronts the fact that she spent more time being cared for by a black woman than her own mother? That would have been real. That would have been something respectful to talk about. Instead, though, she chose to write a fantasy version of the 1960s American South where the racism really isn’t so bad and a white female activist isn’t put into any danger by her activism.

The whole thing is offensive. It’s offensive to black and white women. It’s offensive to black domestic workers of the past and present. It’s offensive to white women who faced real danger and estrangement from their families protesting racism. It’s offensive to the black people who stood up for themselves and fought racism without any white people coming along and telling them they should. And yet people are happily taking the blue pill and revising history.

Thankfully, not everyone is doing that. Slowly Amy and I started to see similar reactions to our own throughout the web. Here are just a few examples:

Indeed, with regard to the white children for whom they cared, black women often felt levels of “ambiguity and complexity” with which our “cowardly nation” is uncomfortable. Yes, my grandmother had a type of love for the children for whom she cared, but I knew it was not the same love she had for us. (Shakesville)

The Help is billed as inspirational, charming and heart warming. That’s true if your heart is warmed by narrow, condescending, mostly racist depictions of black people in 1960s Mississippi, overly sympathetic depictions of the white women who employed the help, the excessive, inaccurate use of dialect, and the glaring omissions with regards to the stirring Civil Rights Movement in which, as Martha Southgate points out, in Entertainment Weekly, “…white people were the help,” and where “the architects, visionaries, prime movers, and most of the on-the-ground laborers of the civil rights movement were African-American.” The Help, I have decided, is science fiction, creating an alternate universe to the one we live in. (Roxanne Gay)

And indeed, the stories of black domestic workers during the Civil Rights Movement are compelling narratives that deserve to be told. But by telling them through the lens of the benevolent white onlooker (Emma Stone’s “Skeeter” in The Help, who records the stories of the maids), it dilutes the message and impact. The black women who struggled during that time are strong enough to stand on their own. They don’t need an interpreter to serve as a buffer between them and the audience, to make their experiences more palatable for today’s viewers. (Kimberley Engonmwan)

It’s frustrating because in these narratives—written by privileged Whites—Black people are always passive. Things are done to them or for them, but they are never the agents of their own liberation. (And sorry, but no, telling the Nice White Lady about your shitty boss isn’t being an agent of your own liberation—not when Black women were actually organizing against Jim Crow, segregation, lynchings and violence, and the intimidation of Black voters.) (Feministe)

What really pushed it over the edge for me, though, and got me going from stewing to activisting (that is a word because I say so) was when someone tweeted a link to the American Black Women Historian’s response to The Help that is not only eloquently put, but also includes a suggested reading list at the end. The reading list got my wheels turning and next thing I knew I was emailing Amy to suggest we do something with that list.

What the Project Is

There are 10 books on the suggested reading list, 5 fiction and 5 nonfiction. For the next five months we will be hosting a project to read one fiction and one nonfiction book and discuss the content and issues raised. One blogger will host each book. For the first month, Amy will be hosting the nonfiction book, and I will be hosting the fiction book. Other bloggers with an interest in the project are welcome to host! Just email me and (opinionsofawolf [at] gmail [dot] com) and Amy (amy.mckie [at] gmail [dot] com) to let us know your interest and what book you might like to host the discussion for.

The fiction book will be discussed on the second Saturday of the month, and the nonfiction book will be discussed on the fourth Saturday of the month. The first Saturday of the month will wrap-up the previous month’s discussions and announce the next two books.

So next Saturday I will be discussing A Million Nightingales by Susan Straight. Please come join in the discussion! You don’t have to read the book to engage in the discussion, but I highly encourage you to do so.

On the 24th, Amy will be discussing Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women , Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Presentby Jacqueline Jones.

We encourage you to join in with us on the project to stop letting people revise history. Get to know the facts behind the history of black domestic workers in the United States and read fictionalized accounts of the experiences written black writers, all recommended by educated historians.

Books of the Project

Fiction:

Like One of The Family: Conversations from a Domestic’s Life, Alice Childress

The Book of Night Women by Marlon James

Blanche on the Lam by Barbara Neeley

The Street by Ann Petry

A Million Nightingales by Susan Straight

Non-Fiction:

Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household by Thavolia Glymph

To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War by Tera Hunter

Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women , Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Presentby Jacqueline Jones

Living In, Living Out: African American Domestics and the Great Migration by Elizabeth Clark-Lewis

Coming of Age in Mississippi by Anne Moody

Bloggers’ Alliance of Non-fiction Devotees (BAND): August Discussion: How Did You Get Into Non-fiction?

Hi guys! It’s hard to believe a month has gone by already since our very first non-fiction discussion in July. This month Amy is hosting, and she asks us how did we get into non-fiction?

I actually found myself baffled by this question. Um, I don’t remember not reading non-fiction? I was raised very religious, although I’m now agnostic, as most of you know. Anyway, because my parents were religious, I was encouraged (strongly) to read my Bible every day. That combined with the kid versions of the Bible were probably my earliest forays into what is technically considered non-fiction. *coughs, coughs*

My earliest memories of non-fiction reading that wasn’t connected to religion is a toss-up between cats, airplanes, and westward expansion. I was fascinated with all three, although cats probably won. I had an ongoing campaign from when I could speak until the age of seven to get a cat when my parents finally caved. I used to wreak havoc in the non-fiction section of the library taking out every single book on whatever topic fascinated me at the moment.

My love of non-fiction definitely played into my first choice of major in undergrad–History with a focus on US History. These classes consisted almost entirely of reading primary documents, and I loved it. I was also finally surrounded by other people my age who felt the same excitement at reading non-fiction as I did. So you see, I never really “got into” non-fiction. I was born that way. Haha.

Check out the non-fiction books I’ve reviewed and discussed since the July discussion:

Bloggers’ Alliance of Nonfiction Devotees (BAND): July Discussion: Favorite Type of Nonfiction

Hi guys! So the lovely Amy (of Amy Reads) let me know of a new organization of bloggers who love to read nonfiction–Bloggers’ Alliance of Nonfiction Devotees. The group has a tumblr, and basically the various members will post links to their reviews of nonfiction books as well as participate in themed discussions once a month. You all know that I definitely partake in nonfiction periodically, so I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to be involved!

This month’s topic is our favorite type of nonfiction. I’d be hard-pressed to choose just one, so I’m going to cheat a bit and talk about, well, three of them.

First, the type of nonfiction that I continued to read even when working full-time and attending grad school at night was memoirs. Memoirs hold a special allure for me. Nothing connects me to people from different walks of life than mine quite like reading their first-hand account of their own life. I especially love memoirs by people who suffer from mental illnesses or have survived abusive situations. Memoirs simply never fail to touch me, even if I disagree with the author on a lot of points. It is truly astounding how different and yet the same we all are.

Second, I love books on health for the layman, particularly books on vegetarianism and veganism. I have a whole pile of tbr books just waiting for me about the health crisis in the US, such as Diet for a New America and Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health

. Knowledge is power, and we Americans certainly need to take charge of our health.

Finally, I was a history major in undergrad, and history books still appeal to me. Currently I am reading a biography on Heinrich Himmler (the head of the Gestapo). I particularly love history books on Native Americans, westward expansion, the American Revolution, Australia, China, Japan, and WWII.

So that’s the types of nonfiction I love! What about you, my lovely readers?