Archive

Book Review: The Dragon from Chicago: The Untold Story of an American Reporter in Nazi Germany by Pamela D. Toler

Discover the untold story of Sigrid Schultz, the fearless American journalist who exposed the rise of Nazi Germany—at a time when women were underrepresented in jouranlism.

Summary:

Schultz was the Chicago Tribune ‘s Berlin bureau chief and primary foreign correspondent for Central Europe from 1925 to January 1941, and one of the first reporters—male or female—to warn American readers of the growing dangers of Nazism.

Drawing on extensive archival research, Pamela D. Toler unearths the largely forgotten story of Schultz’s years spent courageously reporting the news from Berlin, from the revolts of 1919 through Nazi atrocities and air raids over Berlin in 1941. At a time when women reporters rarely wrote front page stories, Schultz pulled back the curtain on how the Nazis misreported the news to their own people, and how they attempted to control the foreign press through bribery and threats.

Review:

This wasn’t on my TBR or wishlist, but when I saw the cover and subtitle at the library, I had to pick it up. I love a troublemaking woman journalist trope—and this was that trope in real life, plus WWII! This nonfiction history book delivers, and in a reader-friendly way.

Despite its depth, this book reads almost as easily as fiction. The author takes care not to put words in the mouths of historical figures—every direct quote comes from letters, interviews, or official documents—yet the scenes are vivid and easy to follow. Each phase of Sigrid Schultz’s life gets just the right amount of attention, from her childhood in Chicago, to her teen years in Europe, to her time as a pioneering journalist. There’s even a well-developed chapter about her post-journalism years in Connecticut, which many historical biographies tend to gloss over.

When I review historical nonfiction, I like to share a few standout insights without giving away everything—so here’s what stuck with me the most.

Sigrid’s sense of identity was deeply American—despite living abroad from age 8 onward. She was so committed to her citizenship that she turned down a full-ride scholarship for singing because accepting it would have required her to renounce her U.S. citizenship.

Her personal life was shaped by loss. Sigrid lost her fiancé in WWI and her second great love to illness in the 1930s. It’s a stark reminder of how much death and grief defined the early 20th century. She didn’t choose to be an independent woman supporting herself and her mother—it was a necessity.

The 1916–1917 German food crisis led to absurd propaganda. Wartime shortages meant that Germans were forced to survive almost entirely on rutabagas. The government tried to spin it, dubbing them “Prussian Pineapples” and publishing recipes for rutabaga soups, casseroles, cakes, bread, coffee, and even beer (yes, rutabaga beer). (📖 page 17).

Although Sigrid’s reporting on the Nazis’ rise to power was the most gripping part of the book—especially during the 1936 Berlin Olympics, when the world was watching—what lingered with me was the story of her later years.

After WWII, Sigrid lost out on professional opportunities because she opposed the Allied occupation of Germany, believing that “any army of occupation is apt to be fascist in its tendencies”—regardless of the occupier’s intent. While I support people having strong ethical stances, her unwavering focus on this issue contributed to a series of choices that prevented her from adapting to the postwar world.

She struggled to transition from journalism to writing for magazines and books, finding it difficult to adjust her style. While the world moved on to focus on the Red Scare, she remained laser-focused on the rise of fascism, convinced it would resurface again. Her stubbornness and focus were, in many ways, her strengths—she even fought off eminent domain in Connecticut, keeping her home from being turned into a parking lot until her death. But they were also a hindrance. It’s real food for thought: when should we adapt, and when should we hold our ground? The balance between the two can shape an entire life.

The book primarily touches on diversity through Sigrid’s observations of the Jewish persecution during the rise of the Nazi regime. Unlike figures such as Corrie ten Boom or Oskar Schindler, she wasn’t someone routinely saving Jewish lives—but she did take small, meaningful actions when possible. One notable example: she convinced a friend to “buy” a Jewish man’s library, allowing him to falsely appear financially stable enough to get a green card—effectively saving his life.

She was also among the first reporters at the liberation of concentration camps and covered the Dachau war crimes trials. The book also explores the possibility that her mother was secretly Jewish, though it remains uncertain.

That said, the book is overwhelmingly told through a white woman’s lens, with little focus on wider global perspectives beyond Sigrid’s own.

Overall, this is an engaging, accessible read, written for popular audiences rather than academic historians. It offers fresh insights into WWII journalism, even for those already familiar with the era, and provides a fascinating look at a pioneering woman in media history. Recommended for readers interested in WWII, investigative journalism, and women’s history. For a more lighthearted take on trailblazing women in journalism, check out Eighty Days, the story of investigative journalist Nellie Bly’s race around the world.

If you found this review helpful, you might also enjoy my podcast, where I explore big ideas in books, storytelling, and craft. You can also support my work by tipping me on ko-fi, browsing my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral/coupon codes, or signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter. Thank you for supporting independent creators!

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 288 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

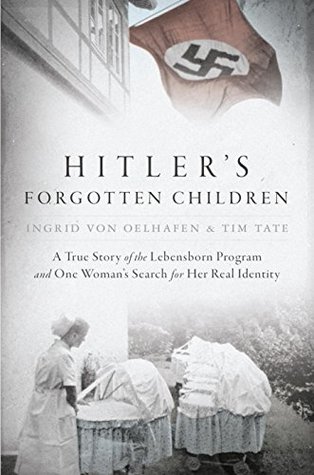

Book Review: Hitler’s Forgotten Children by Ingrid von Oelhafen and Tim Tate

Summary:

Created by Heinrich Himmler, the Lebensborn program abducted as many as half a million children from across Europe. Through a process called Germanization, they were to become the next generation of the Aryan master race in the second phase of the Final Solution.

Ingrid is shocked to discover in high school that her parents are actually her foster parents and struggles, like many in post-war Germany, to get official documentation of who she is. When the Red Cross contacts her, she slowly starts to realize her connection to the Lebensborn program. Though the Nazis destroyed many Lebensborn records, Ingrid unearths rare documents, including Nuremberg trial testimony about her own abduction.

Review:

There can sometimes be this misconception that society immediately dealt with all of the fall-out of WWII. Germany does do an admirable job of directly confronting genocide and fascism. But, as this book demonstrates, not everything was in fact dealt with right away. There were intentions to, but other things like the Cold War got in the way. One of the things that got swept under the rug until the early 2000s (!!) was the Lebensborn program.

Ingrid speaks eloquently about the rumors in the 90s especially about an SS “breeding program.” I actually remember hearing these rumors. Ingrid does a good job of describing how she felt realizing she might have a connection to Lebensborn in the face of these rumors. In fact, there was no “breeding program” aspect to Lebensborn. At least, not in the way the rumor mill said it. Women were not kept in breeding houses with SS members sent to them. But women were encouraged to sleep with SS members, regardless of their own coupled or marital state, to make more Aryan babies for Hitler. Where Lebensborn came in was that if a pregnant woman and the father of the baby fit the Aryan bill sufficiently, she could come to Lebensborn to be cared for until her baby was born. Then she might keep the baby or she might give it to “suitable” foster parents, usually high-ranking officials.

But the actual war crime part of Lebensborn was the other aspect. The SS abducted children from largely Eastern European occupied territories, sending them to Lebensborn to be Germanized and given to foster parents. They literally would put out a call ordering all families to report with their children to a center, check them for “racially desirable” qualities, and then take the children that “had potential” for Germanization, returning the rest. They also used this as a punishment against resistance fighters, only they would abduct all of their children, sending the “undesirable” ones to work camps and the rest to Lebensborn. It’s this latter aspect of Lebensborn that Ingrid discovers her connection to.

The book begins with a scene of a child abduction and then switches to Ingrid’s memories of her early life immediately post-war and her discovery that she was a foster child. Then many decades are skipped because in reality Ingrid discovered nothing new about her childhood until she was an older woman starting to think about retirement. The earliest part of the book is quite engaging because her foster mother escapes from East to West Germany right before the Iron Curtain closes. The rest is engaging because, of course, we are alongside with Ingrid as she discovers the truth of her early life.

Ingrid’s early investigations in the early 2000s are hampered by intentional resistance and red tape. Even though on paper it should have been easy for her to get assistance going through the voluminous archives (the Nazis kept meticulous records of everything), she actually met foot dragging and even downright lies from those who should have been helping her. Essentially, some people didn’t want the truth of Lebensborn to get out. But Ingrid finds help along the way from those who want to see the truth come out and justice, what little is available at this point in time, done.

Ingrid is quite honest about her difficult feelings during all of this. She ultimately decides she’s not defined by her origins. While I absolutely agree that “the choices we make throughout our life” (page 267) are essential in defining us, I also think where we come from does as well. The two go hand-in-hand. It saddens me that she seems to need to distance herself from that, although I understand why it helps her to do so.

Overall, this is an engaging book that is a quick read. The pairing of the historical facts with the memoirs of an innocent person who discovers her connection to this program works well for the delivery of these facts. It helps the reader remember that these were real events impacting real people who were just starting to discover the truth of their early childhood in the early 2000s.

If you found this review helpful, please consider checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral/coupon codes, or tipping me on ko-fi. Thank you for your support!

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 276 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: purchased

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Book Review: Heinrich Himmler: The Sinister Life of the Head of the S.S. and Gestapo by Roger Manvell and Heinrich Fraenkel

Summary:

Summary:

Manvell and Fraenkel conducted years of meticulous research both with primary documents and those who actually knew Himmler to bring about a biography of the man infamous for being in charge of the S.S., Gestapo, and concentration camps that made the terror of Hitler’s reign possible. They seek to provide a well-rounded look at Himmler’s entire life for those with some familiarity with the events of World War II.

Review:

This was a fascinating and difficult book to read, not because of the writing style or the atrocities recounted, but because the authors succeeded in putting a human face on Heinrich Himmler. In the intro to the book, the authors state:

The Nazi leaders cannot be voided from human society simply because it is pleasanter or more convenient to regard them now as outside the pale of humanity. (location 31)

In other words, the easy thing to do is pretend the Nazi leaders or anyone who commits atrocities is something other than human. That they are monsters. When in fact, they really are still people like you and me, and that should frighten us far more than any monster story. What leads people to do horrible things to other people? What makes them bury their conscience and humanity and commit acts of evil? This biography thus does not say “here is a monster,” but instead says, “Here is this young boy who became a man who committed himself to a cause and proceeded to order acts of evil upon others. What forces came together to mold him into someone who would do these things?”

One of the more fascinating things brought to light in this book is that Himmler was never actually fit into the ideal of a top-notch Aryan male he himself advocated. In fact throughout his life he was sickly, pale, and scholarly. He tried in school to fit in with the athletic boys but never succeeded in anything for any length of time except fencing. Instead of accepting who he was, he continually pushed his sickly body past its limits throughout his life, trying to force it to fit into his ideals of what it should be. He actually enlisted his own personal healer, a masseuse trained by a talented Chinese doctor, throughout the war. This masseuse, Kersten, was working as a spy for the Allies and was instrumental in convincing Himmler to release various people from concentration camps throughout the war. His sickly body then not only opened him up to the Allies for a convenient spy, but also was key in how he related to the world. He projected his own insecurities about the ideal body onto everyone else.

Himmler’s anxiety to destroy the Jews and Slavs and place himself at the head of a Nordic Europe brash with health was a compensation for the weakly body, the sloping shoulders, the poor sight and the knock-knees to which he was tied. (location 2189)

This physical weakness and obsession does not mean he was a weak man, however. He was profoundly intelligent and detail-oriented. He easily became obsessed with ideas he came up with and would search for proof of them excluding any and all evidence to the contrary. Those of us who went to liberal, private colleges where we were taught to adjust our worldview for new, challenging ideas may be surprised to learn that Himmler read obsessively. The fact though is that Himmler sought out in his reading sources that would simply support his previously established, prejudicial worldview.

Like Hitler, he [Himmler] used books only to confirm and develop his particular prejudices. Reading was for him a narrowing, not a widening experience. (location 2547)

Thus we cannot depend on reading alone to prevent close-mindedness.

As the Nazi regime continued on, Himmler grew more and more committed to his obsessions. Those who knew him well described the frenzy and meticulousness with which he worked over every detail toward his final goal of the “Aryan race” being in control of Europe.

Himmler’s need to rid himself of the Jews became an obsession. The ghosts of those still living haunted him more than the ghosts of those now dead; there were Jews everywhere around him, in the north, in the west, in the south, in the areas where his power to reach them was at its weakest. (location 2074)

The information on Himmler at this time period certainly sound like a man suffering from intense paranoia. Think of John Nash in A Beautiful Mind and how he firmly believed government agents were all around him persecuting him. The difference is that this physically weak, close-minded, paranoid man was given immense power over the lives of millions instead of simply being a professor. It is easy after reading this book to see how Himmler could easily have been that crazy neighbor worried that the people across the street were watching him all the time instead of the engineer behind genocide. All it took was placing near total power and trust in his hands to turn him into the organizer of a genocide.

There will always exist human beings who, once they are given a similar power over others and have similar convictions of superiority, may be tempted to act as he [Himmler] did. (location 592)

The lesson the authors send home repeatedly then is that Himmler was just a man overcompensating for a physically weak body who grasped onto the idea that he was actually superior to others simply because of his ancestors with a tendency toward paranoia who was given a dangerous amount of power. It is easy to imagine how the entire situation could have worked out differently if some sort of intervention had happened earlier in his life. If he was taught that everyone was valuable for different reasons that have nothing to do with their physical abilities or ancestry. If he had initially read books that weren’t racist and xenophobic. If he was never swept into the Nazi Party mania in the 1930s. If he had been maintained as an office worker in the Nazi party instead of being given so much power. It’s a lot of if’s, I know, but it’s important to think about all the ways to prevent something like this from ever happening again. Although the authors’ primary point is “be careful who you allow to have power,” I would also add “intervene when they are young to prevent the development of a xenophobic, paranoid personality to start with.” With both precautions in place, perhaps we humans as a group can avoid such atrocities in the future.

Readers should note that this book is written by Europeans and not “translated” into American English. Additionally, periodically the authors sway from the strict chronological method of a biography to follow one thought or event through to its conclusion then back-track. This was a bit distracting, but absolutely did not prevent me from learning much about Himmler, WWII, and the Holocaust that I did not previously know.

Overall, I highly recommend this to those with an interest in WWII in particular, but also to anyone interested in the prevention of future genocides. It offers great insight into how these atrocities came to be.

4 out of 5 stars

Source: Amazon (See all Third Reich History Books)

Movie Review: The Nightmare Never Ends (1980)

Summary:

Summary:

A devout Catholic woman married to an atheist professor who has just published a book called God is Dead starts having nightmares about Nazis and dead people in the water. Meanwhile, a Jewish hunter of Nazi war criminals shows up mysteriously murdered with his face ripped off and the numbers “666” tattooed on his chest. The tenuous connections between these two soon reveal a dark presence on the planet.

Review:

This movie can best be summed up in the phrase: Satan at the Disco. Satan is not just alive and beautiful (not handsome, beautiful) but is a disco-going playboy complete with a harem of hypnotized women who actively participated in Nazi atrocities back in the day. In spite of Satan’s presence at the disco, I found myself wanting to go there. I have to say, it certainly seemed more appealing than Tequila Rain on Lansdowne Street.

This film is an odd mix of things done well and things done horribly badly. The special effects are surprisingly good for the time with certain scenes managing to surprise and/or gross out my friend and myself. Of note is one particular scene where a character’s eyeball pops out from his head. Quite gruesome for the special effects of the time. On the other hand, the actress playing the Catholic woman cannot act to save her life. She can, however, scream quite well, which is apparently what she was hired for. The plot is creative and features a fun twist at the end, but it wanders around a bit too much and is confusing for about the first 40 minutes of the film. It needed some serious editing before being filmed. Similarly, the set designers clearly had no comprehension of Jewish culture at all as they decided to show that the Jewish man’s ethnicity by randomly having a fully-loaded menorah ever-present on his nightstand. *face-palm*

In spite of these shortcomings though, the story is still unique enough that the film is enjoyable, particularly if you enjoy bad horror with a touch of classic 1970s disco. I therefore recommend it to the tiny percentage of the population for which both of those statements holds true.

3.5 out of 5 stars

Source: Gift