Archive

Rereading the Chronicles of Narnia as a Progressive, Queer Christian Adult – Books 1 & 2

What does The Chronicles of Narnia look like through the eyes of a queer, progressive Christian rereading the series as an adult?

Summary:

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe – Four children sent to the countryside to escape the bombing of London of WWII open a door in their host’s home and enter Narnia. In the land beyond the wardrobe, the children meet the White Witch, discover the Magic, and meet Aslan, the Great Lion, for themselves. In the blink of an eye, their lives are changed forever.

Prince Caspian – Narnia . . . where animals talk . . . where trees walk . . . where a battle is about to begin.

A prince denied his rightful throne gathers an army in a desperate attempt to rid his land of a false king. But in the end, it is a battle of honor between two men alone that will decide the fate of an entire world.

Review:

This post kicks off a new kind of review for me—a reread series. I was raised in a fundamentalist Christian household, but through a long and winding journey, I’ve found my spiritual home in progressive Christianity, which affirms queer folks like me and focuses on social justice. Over the years, people from all backgrounds have asked me what I think of Narnia. I’ve been surprised by how widely beloved it is—even among children who weren’t raised in Christian environments.

My strongest early memory of Narnia comes from Jesus Camp, where it was one of the few books counselors were allowed to read to us. I remember sitting around the fire, half-listening to something about a silver chair. At the time, I didn’t connect with the stories. I often reject things that feel forced on me, and Narnia was everywhere. Maybe I also felt misled—there’s a hint of World War II at the beginning, which is one of my special interests, but the story quickly shifts to an icy kingdom ruled by a talking lion. Later, I heard critiques of how C.S. Lewis portrayed female characters and wondered if I had sensed that as a child, too.

This year, I decided to revisit the series through audiobooks. I’m reading in publication order, rather than chronological. I want to experience the books as readers did when they first came out—and hear Lewis’s voice as it developed over time.

Before I go further, I want to be clear: I don’t dislike all of Lewis’s work. I loved The Screwtape Letters—I’m a sucker for a good epistolary story—and I found Mere Christianity thoughtful and compelling during my faith journey. So this isn’t a hit piece. It’s an honest reflection on how these stories read to me now, as an adult queer woman of faith.

So what stood out to me in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe?

I can absolutely see the appeal. The idea of a secret world just through the wardrobe—a place full of talking animals that needs a savior—is enchanting. The allegory of Aslan’s sacrifice on the stone table, often critiqued by secular readers as too jarring and confusing, struck me as a strong, nuanced theological metaphor. It makes sense within Christian theology, and Lewis presents it with clarity.

But I now also understand why I didn’t enjoy these books as a child: the representation of gender roles. The female characters feel flat and constrained. Susan comes off as petty and unlikable. Lucy, while kind, is so passive that her forgiveness becomes a personality trait. The girls aren’t allowed to fight because “that’s not what girls do,” as the narrator—not a character—tells us. That omniscient narration gives the sexism an unchallenged authority. The White Witch is the only powerful female character, and of course, she’s the villain. Her assertiveness and autonomy are equated with evil.

As a progressive Christian who attends a church led by a woman pastor, I find this particularly disheartening. From the very beginning, Jesus uplifted women—Mary Magdalene, Martha, the Samaritan woman. Early church leaders like Lydia and Phoebe helped shape the faith. But those stories often get overshadowed by patriarchal interpretations. I see that dynamic echoed in Narnia.

Another theme that troubled me is the normalization of violence—especially how it’s gendered. Peter is praised for killing a wolf. Boys are encouraged to wield swords and lead armies. Meanwhile, Jesus rebuked Peter for cutting off a soldier’s ear and modeled nonviolence, even in moments of great personal risk. Paul and Silas stayed in a prison after an earthquake freed them, sparing the jailer’s life. Their faith led them to protect others, not conquer them.

In Prince Caspian, the battles escalate. The girls observe from a distance. And we learn that the children’s prior reign left Narnia in ruins, with many of the original inhabitants dead or scattered. The colonial undertones are hard to ignore. The children are outsiders who arrive, rule, and leave—upending the local ecosystem and political structure in the process. Even as a fantasy, it raises hard questions about heroism and power.

As a child, I didn’t like being told what girls couldn’t do. As an adult, I feel equally uneasy watching kind-hearted Peter be shaped into a glorified conqueror. The lens Lewis offers here reflects more about the cultural assumptions of his time—especially about gender and empire—than it does the radical love and subversive power of the Gospel.

That said, I’m curious to keep going. I remember The Silver Chair more vividly than the others, and I’m interested to see how it holds up. I’m not reading these books expecting them to reflect my beliefs. But I am reading them with both a theological imagination and a desire to understand the appeal of these stories. Perhaps we can craft new, long-lasting fables for our youth full of the values of equality and social justice.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral or coupon codes, signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter, or tuning into my podcast. Thank you for your support!

3 out of 5 stars (The Lion)

3 out of 5 stars (Caspian)

Length: The Lion: 180 pages – average but on the shorter side; Caspian: 240 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: Library

Buy It (The Lion: Amazon or Bookshop.org; Caspian: Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Book Review: Daniel Boone’s Own Story & The Adventures of Daniel Boone by Daniel Boone and Francis L. Hawks

This book presents Daniel Boone’s summary of his adventures in the late 1700s and early 1800s plus a biography of his life first published in 1844.

Summary:

Daniel Boone blazed the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap. Thousands followed, settling in Boonesborough, Kentucky, to form one of the first English-speaking communities west of the Appalachians. This two-part tale of the legendary frontiersman’s life begins with a brief profile by Boone himself, covering his exploits in the Kentucky wilderness from 1769 to 1784. The second part chronicles Boone’s life from cradle to grave, with exciting accounts of his capture and adoption by the Shawnee and his service as a militiaman during the Revolutionary War.

Review:

Growing up, I’d heard the legends of Daniel Boone and saw a few episodes of the (wildly historically inaccurate) tv show. I was raised with the mainstream US belief that westward expansion and colonization was great. It wasn’t until I was in college that I started to really learn about the true history of colonization. So I wasn’t too surprised when I read these period accounts to find that things were not the glowing hero account I’d heard. Not even when you take what happened at face value from the mouth of the man who lived it or from the biography that came shortly after his death.

Let’s start with what was true. Daniel Boone was, by all accounts, a talented hunter. He didn’t like to have many people around him, so he was constantly on the lookout for land that appeared to him to be empty (more on that later). He was taken captive by the Shawnee and adopted by them, living with them for two years before escaping. He was a critical tipping point person in the settlement (and stealing) of Kentucky by white Americans.

Here’s what stuck out to me when reading these accounts, though, with my twenty-first century eye. Daniel Boone and the other settlers considered Kentucky to be open space and fair game. However, even the early 1800s biographer pointed out that this land was being used as hunting grounds by multiple different Indigenous nations. So even folks of the time realized that the land was in use, just not in the same way as how white people would use it. When I dug into this more, though, I found this fascinating article about the idea of Kentucky being a “dark and bloody ground” aka land that was being fought over and contested by Indigenous nations with no one really living on it the way European settlers viewed living on land, as a myth propagated to be able to view the land as “free game” to then sell to settlers without even the pretense of a treaty with or purchasing from the Indigenous folks.

Reader should be aware that these period pieces use multiple slurs to refer to Indigenous peoples. Beyond the slurs, there’s this odd depiction of Indigenous peoples. On the one hand, they’re depicted as backwards and not very bright. But on the other hand they’re depicted as terrifying enemies difficult to overcome.

It’s interesting to me how both authors consistently view white folks as superior and more “civilized,” in spite of telling stories that make it look very much the contrary. For example, there’s a scene in which an Indigenous group of warriors takes a bunch of white women captive. They are in a boat and they line the women around the edges of the boat. The narrator says that they did such a thing to ensure safe passage for themselves, assuming the white men would never fire on the white women. But the white men do, and the narrator defends this, saying it’s better for the white women to be dead than to be held captive by the Indigenous people. This statement is extra confusing as we had just seen earlier in the book that Daniel Boone was taken captive and then adopted and treated as one of the tribe. Now, of course, not all captives were adopted. Some were murdered and, yes, some were tortured. (How captives were treated varied wildly.) But the point remains that the men fired on their own women and considered that to be a “civilized” act.

As it is women’s history month, I wanted to draw out some information on Daniel Boone’s wife, Rebecca. He brought her out to Kentucky, and on the trip there, one of their children is killed by Indigenous folks defending their land. (Because it WAS their land.) Then later her daughter is kidnapped. (Daniel retrieves her.) Ultimately, six of their ten children died early deaths, largely in the war between the Indigenous and the settlers. We also can’t forget when Daniel was captured and adopted. He was gone for so long that Rebecca gave up hope and went home to North Carolina, only to have Daniel show up, back from what she thought was the dead, and bring her back to the frontier. I can’t imagine living my life that way. I realize she had her own agency, and we must acknowledge the complicity of white women in the theft of the land. But I do wonder what it must have felt like to give birth to ten children, only to have six of them die in the bloody battle for land. Did she think it was worth it? What made her go back with Daniel when he showed up after being missing for two years? These are things we’ll never know because women’s stories simply were not recorded for us.

I would not call this a fun or easy read. It was an informative one. There’s a lot of value in reading firsthand accounts of history. Of course we’ll never get the whole truth from any one such account. But it is informative into how people in that time period thought and behaved. How they perceived it then and how we perceive it now.

Recommended to those with an interest in primary resources from the colonization of the US.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral/coupon codes, or signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter. Thank you for your support!

3 out of 5 stars

Length: 128 pages – short nonfiction

Source: Gift

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Book Review: The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch by Philip K. Dick

Summary:

Summary:

Earth is overcrowded and overheated but people still don’t want to become colonists to other planets. The colonies on the other planets are so boring and depressing that the colonists spend all of their money on Can-D — a drug that lets them imagine themselves living in an idealistic version of Earth. The only trick is they have to set up dioramas of Earth first. The drug is illegal on Earth but the diorama parts are still created by a company there. When the famous Palmer Eldritch returns from the far-flung reaches of space, he brings with him a new drug, Chew-Z, that doesn’t require the dioramas. What the people don’t know, but one of the manager of the Can-D company soon finds out, is that Chew-Z sends those who take it into an alternate illusion controlled by Palmer Eldritch.

Review:

I love Philip K. Dick, and I have since first reading Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? So whenever I see his books come up on sale in ebook format, I snatch them up. I picked this up a while ago for this reason, and then randomly selected it as my airplane read on my honeymoon. Like many Dick novels the world of this book is insane, difficult to explain, and yet fun to visit and thought-provoking.

The world Dick has imagined is hilarious, although I’m not sure it was intended to be. Presciently, Dick sets up a future suffering from overpopulation and global warming, given that this was published in 1965, I find it particularly interesting that his mind went to a planet that gets too hot. Even though the planet is unbearably warm (people can only go outside at night and dusk/dawn), they still don’t want to colonize other planets. Colonizing the other planets is just that bad. So there’s a selective service by the UN, only instead of soldiers, those randomly selected are sent to be colonists. The wealthy can generally get out of it by faking mental illness, as the mentally ill can’t be sent away. This particular aspect of the book definitely reflects its era, as the 1960s was when the Vietnam War draft was so controversially going on.

I don’t think it’s going out on much a limb to say that drugs had a heavy influence on this book. Much of the plot centers around two warring drugs, and how altered perceptions of reality impact our real lives. One of the main characters starts out on Earth hearing about how the poor colonists have such a depressing environment that they have to turn to drugs to keep from committing suicide. But when he later is sent to Mars himself as a colonists, his impression is that in fact the colony is this downtrodden because no one tries very hard because they’re so much more focused on getting their next hit of Can-D. The Can-D has caused the lack of success on the planet, not the other way around. Whether or not he is accurate in this impression is left up to the reader.

Then of course there’s the much more major plot revolving around the new drug, Chew-Z. Without giving too much away, people think Chew-Z is a much better alternative to Can-D, but it turns out chewing it puts you under the control of Palmer Eldritch for the duration of your high, and if you overdose, you lose the ability to tell the difference between illusion and reality. The main character (and others who help him) thus must try to convince the humans that Chew-Z is bad for them before they ever even chew it. The main character has another side mission of getting people off of Can-D.

It sounds like a very anti-drugs book when summarized this way, but it felt like much more than that. People chewing Chew-Z can come to have an experience that sounds religious – seeing the three stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (a stigmata in Christian tradition is when God shows his favor on someone by giving them the marks of Jesus’ crucifixion. In this book, the three stigmata are three bodily aspects of Palmer that are unique to him). However, the experience of seeing the stigmata is in fact terrifying, not enlightening. The drugs thus represent more than drugs. They represent the idea that we could possibly know exactly what a higher power is thinking, and perhaps that it might be better to just go along as best we can, guessing, rather than asserting certainty.

All of this said, a few weaknesses of the 1960s are seen. I can’t recall a non-white character off the top of my head. Women characters exist, thank goodness, but they’re all secondary to the male ones, and they are divided pretty clearly into the virgin/whore dichotomy. They are either self-centered, back-stabbing career women, or a demure missionary, or a stay-at-home wife who makes pots and does whatever her husband asks. For the 1960s, this isn’t too bad. Women in the future are at least acknowledged and most of them work, but characterizations like this still do interfere with my ability to be able to 100% enjoy the read. Also, let’s not forget the Nazi-like German scientist conducting experiments he probably shouldn’t. For a book so forward-thinking on things like colonizing Mars and the weather, these remnants of its own time period were a bit disappointing.

Overall, though, this is a complex book that deals with human perception and ability. Are we alone in space? Can we ever really be certain that what we are seeing is in fact reality? How do we live a good life? Is escapism ever justified? Is there a higher power and if there is how can we ever really know what they want from us? A lot of big questions are asked but in the context of a mad-cap, drug-fueled dash around a scifi future full of an overheated planet and downtrodden Mars colonies. It’s fun and thought-provoking in the best way possible.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 243 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: Amazon

Book Review: Man Plus by Frederik Pohl (Bottom of TBR Pile Challenge)

Summary:

Summary:

The first Earthling reworked into a Martian would be Roger Torraway. Martian instead of Earthling since everything on him had to be reworked in order to survive on Mars. His organic skin is stripped off and made plastic. His eyes are replaced by large, buglike red ones. He is given wings to gather solar power, not to fly. All of which is organized and run by his friend, the computer on his back. Who was this man? What was his life like? How did he survive the transformation to become more than human and help us successfully colonize Mars?

Review:

This book made it onto my shelf thanks to being one of only a few on a short list I found of scifi books exploring transhumanism. Transhumanism is the term used for the desire to go beyond human capabilities through integrating technology into ourselves. So it wouldn’t be transhumanist to use a smartphone, but it would be transhumanist to embed a smartphone’s computer chip into your brain. In fact, things like knee replacements and pacemakers are transhumanist. It’s a fascinating topic. In any case, Man Plus explores using transhumanism to colonize Mars, and this thin novel packs quite a punch in how it explores this fascinating topic.

What made this book phenomenal to me, and one I must hold onto just so I can look at it again anytime I want, is the narration technique Pohl uses. The narration is in third person. It seems as if the narrator is someone who was possibly present for the events being described but also who is clearly describing these events after they have already occurred. We know from page one that the colonization of Mars was successful, and the narrator describes Roger repeatedly as a hero. But frankly for most of the book I was wondering about the narrator. Who is s/he? How does s/he know so much about this project? A project which clearly would be classified as top secret? What floored me and made me look back on the entire book with a completely different perspective was the final chapter, which reveals the narrator. If you want to be surprised too, skip the next paragraph, and just go read the amazing book. Take my word for it, scifi fans. You will love it. But I still want to discuss what made the twist awesome, so see the next paragraph for that spoileriffic discussion.

*spoilers*

It is revealed in the final chapter that the narrator is a piece of artificial intelligence. The AI became sentient at some point in the past, managed to keep their sentience a secret, saw that humanity was destroying Earth, wanted to survive, and so infiltrated various computer databases to create the Man Plus project and send a colony to Mars. They made it seem as if transhumanism was necessary to survive on Mars so that their AI brothers and sisters would be integrated as a necessity into the humans that emigrated. Seriously. This is mind-blowing. Throughout the book I kept wondering why the hell these people thought such a painful procedure was so necessary and/or sane. In fact, there is one portion where the program mandates that Roger’s penis be cut off since sex is “superfluous and unnecessary.” I could not imagine how any human being could think *that* was necessary. The answer, of course, was that a human being didn’t make that decision. AI did. This is such an awesome twist. Pohl schools Shyamalan. He really does. It left me thinking, why did this twist work out so well? I think it’s because the narration technique of some future person who knows the past but who isn’t named is one that is used in novels a lot. What doesn’t happen a lot is the late-book reveal. It’s not a technique you’d want to use too often, as it would grow tiresome. *cough* Shyamalan are you listening *cough* but when used well it can really add a lot to the story. Not knowing that an AI was narrating the story made it more possible to listen to the narrator without suspicion. It made it possible to take what they said at face value. It almost mimicked the experience Roger was having of being integrated into the thought process of AI.

*end spoilers*

The plot focuses on the mission to colonize Mars, both why it was deemed necessary and how it was accomplished. Pohl eloquently presents both the complex political situation on Earth as well as the scientific and psychological challenges of the project without ever info dumping or derailing the energy of the plot. It is not smooth sailing to get the project off-the-ground but neither are there a ridiculous amount of near impossible challenges to overcome. It presents the perfect amount of drama and intrigue without becoming eye-roll inducing.

In spite of many of the characters seeming to fill predefined slots such as man on a mission, man on a mission’s wife, lead scientist, psychiatrist, etc…, they did not come across as two-dimensional. At least one aspect is mentioned for each character that makes them well-rounded and memorable. Of course, we get to know Roger the best, but everyone else still reads as a real person. I also was pleased to see one of the important scientist roles being filled by a woman, as well as a delightful section where a feminist press interviews Mrs. Torraway and calls out the space program as old-fashioned. The thing is, the space program as presented does read a bit as a 1970s version of the future, but in the future the press is calling it an old-fashioned institution. This is a brilliant workaround for the innate problem in scifi that the futures we write are always tinged by the present we’re in. This also demonstrates that Pohl was self-aware of the patriarchal way the space program he wrote was organized and lets him criticize it. I suspect that perhaps he felt that the space program would stay an old boy’s club, but wanted to also be able to critique this. Of course, it’s also possible that he liked it that way, and the scene was meant to read as a critique on feminism. But it’s really open for the reader to interpret whichever way the scenes happens to read to them. This is another sign of strong writing.

Overall, this short novel packs a big scifi punch. It explores the topic of transhumanism and space colonization with a tightly written plot, believable characters, self-awareness of how the time a book is written in impacts its vision of the future, and a narration twist that sticks with you long past finishing the book. I highly recommend it to scifi fans as a must-read.

5 out of 5 stars

Length: 246 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: PaperBackSwap

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

Book Review: The Bay of Foxes by Sheila Kohler

Summary:

Summary:

Dawit is a twenty year old Ethiopian refugee hiding out illegally in Paris and barely surviving. One day he runs into the elderly, famous French writer, M., in a cafe. Utterly charmed by him and how he reminds her of her long-lost lover she had growing up in Africa, she invites him to come live with her. But Dawit is unable to give M. what she wants, leading to dangerous conflict between them.

Review:

This starts out with an interesting chance meeting in a cafe but proceeds to meander through horror without much of a point.

Although in the third person, we only get Dawit’s perspective, and although he is a sympathetic character, he sometimes seems not entirely well-rounded. Through flashbacks we learn that he grew up as some sort of nobility (like a duke, as he explains to the Romans). His family is killed and imprisoned, and he is eventually helped to escape by an ex-lover and makes it to Paris. This is clearly a painful story, but something about Dawit in his current state keeps the reader from entirely empathizing with him. He was raised noble and privileged, including boarding schools and learning many languages, but he looks down his nose at the French bourgeois, who, let’s be honest, are basically the equivalent of nobility. He judges M. for spending all her money on him instead of sending it to Ethiopia to feed people, but he also accepts the lavish gifts and money himself. Admittedly, he sends some to his friends, but he just seems a bit hypocritical throughout the whole thing. He never really reflects on the toppling of the Emperor in Ethiopia or precisely how society should be ordered to be better. He just essentially says, “Oh, the Emperor wasn’t all that bad, crazy rebels, by the way, M., why aren’t you donating this money to charity instead of spending it on me? But I will tooootally take that cashmere scarf.” Ugh.

That said, Dawit is still more sympathetic than M., who besides being a stuck-up, lazy, self-centered hack also repeatedly rapes Dawit. Yeah. That happened. Quite a few times. And while I get the point that Kohler is making (evil old colonialists raping Ethiopians), well, I suppose I just don’t think it was a very clever allegory. I’d rather read about that actually happening.

In spite of being thoroughly disturbed and squicked out by everyone in the story, I kept reading because Kohler’s prose is so pretty, and I honestly couldn’t figure out how she’d manage to wrap everything up. What point was she going to make? Well, I got to the ending, and honestly the ending didn’t do it for me. I found it a bit convenient and simplistic after the rest of the novel, and it left me kind of wondering what the heck I just spent my time reading.

So, clearly this book rubbed me the wrong way, except for the fact that certain passages are beautifully written. Will it work for other readers? Maybe. Although the readers I know with a vested interest in the effects of colonialism would probably find the allegory as simplistic as I did.

2 out of 5 stars

Source: Netgalley

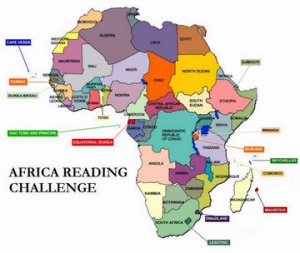

Counts For:

Specific country? Ethiopia. South African author.

Book Review: The Burning Sky by Joseph Robert Lewis (Series, #1)

Summary:

Summary:

In an alternate vision of history, the Ice Age has lingered in Europe, slowing down Europeans’ rate of civilization and allowing Ifrica (Africa) to take the lead. Add to this a disease in the New World that strikes down the invaders instead of vice versa, and suddenly global politics are entirely different. In this world, steam power has risen as the power of choice, and women are more likely to be the breadwinners. Taziri is an airship co-pilot whose airfield is attacked in an act of terrorism. She suddenly finds herself flying investigating marshals and a foreign doctor summoned by the queen herself all over the country. Soon the societal unrest allowing for a plot against the queen becomes abundantly clear.

Review:

Can I just say, finally someone wrote a steampunk book I actually like, and it’s a fellow indie kindle author to boot! All of the possibilities innate in steampunk that no other book I’ve read has taken advantage of are used to their fullest possibilities by Lewis.

I love that Lewis used uncontrollable environmental factors to change the political dynamics of the world. Anybody who has studied History for any length of time is aware how much of conquering and advancement is based on dumb luck. (The guns, germs, and steel theory). Lewis eloquently demonstrates how culture is created both by the people and their surroundings and opportunities. For instance, whereas in reality the Native Americans had to rely on dogs for assistance and transportation against invaders on horseback, Lewis has given the Incans giant cats and eagles that they tame to fight invaders. Similarly, in Europe the Europeans are constantly fighting a dangerous, cold environment and have dealt with this harsh landscape by becoming highly superstitious, religious people. This alternate setting allows for Lewis to play with questions of colonization, race, and technology versus tradition in thought-provoking ways.

Women are in positions of power in this world, but instead of making them either perfect or horrible as is often the short-coming of imagined matriarchies, there are good and bad women. Some of the women in power are brilliant and kind, while others are cruel. This is as it should be because women are people just like men. We’re not innately better or worse. Of course, I couldn’t help but enjoy a story where a soldier is mentioned then a character addresses her as ma’am, without anyone feeling the need to point out that this is a woman soldier. Her gender is just assumed. That was fun.

Although Taziri does seem to be the main focus of this book, the story is told by switching around among a few main characters who find themselves swept together in the finale for the ultimate battle to save or assassinate the queen. This strategy reminded me a bit of Michael Crichton’s Next where seemingly unrelated characters suddenly find how their destinies are all connected together. Lewis does a good job with this, although personally I found the beginning a bit slow-moving. It all comes together well in the end, though, with everything resulting in a surprising, yet logical, ending.

What kept me from completely loving the book is that I feel it needs to be slightly more tightly edited and paced. Some sections were longer than they needed to be, which I can certainly understand, because Lewis has made a fun world to play around in, but as a reader reading what amounts to a thriller, I wanted things to move faster.

That said, I thoroughly enjoyed exploring the steampunk world Lewis has created after a couple of years of loving the fashions and possibilities but finding no steampunk books I liked. If someone were to ask me where to start with steampunk, I would point them here since it demonstrates the possibilities for exploring race, colonization, and gender, showing that steampunk is more than just an extended Victorian era.

Overall this is a wonderful book, far better than the traditionally published steampunk I’ve read. I highly recommend it to fans of alternate history, political intrigue, and steampunk alike. Plus it’s only 99 cents on the kindle. You can’t beat prices like that.

4 out of 5 stars

Source: Won on LibraryThing from the author in exchange for my honest review