Archive

Book Review: Sula by Toni Morrison

A lyrical and haunting novel about two Black women whose lifelong friendship is tested by betrayal, love, and the weight of their small-town community’s judgment.

Summary:

Sula and Nel are two young black girls: clever and poor. They grow up together sharing their secrets, dreams and happiness. Then Sula breaks free from their small-town community in the uplands of Ohio to roam the cities of America. When she returns ten years later much has changed. Including Nel, who now has a husband and three children. The friendship between the two women becomes strained and the whole town grows wary as Sula continues in her wayward, vagabond and uncompromising ways.

Review:

This was my second Toni Morrison novel—the first being The Bluest Eye, which I read back in college. Morrison’s prose is deeply lyrical, which makes her books swift reads on the surface, even when they delve into painful and challenging themes. Sula is no exception.

Each chapter is titled with the year it takes place in, but only covers a brief vignette from that year. Despite spanning several decades, this is a short novel, structurally and in page count. Though the title suggests a singular character focus, Sula is as much about a place—the Bottom, a Black neighborhood in a Southern state situated on the hillside, land the white residents had no interest in. The reason for its ironic name is revealed in the first chapter through a racist tale, setting the tone for the book’s critique of systemic racism.

Indeed, one of the novel’s most striking accomplishments is how clearly it shows that systemic racism ruins lives, whether characters comply with social expectations or resist them. For me, Nel represents compliance while Sula represents defiance—yet neither of them leads a life free from pain. Every person in their orbit suffers in some way, and that suffering is deeply entangled with the racist systems surrounding them.

The edition I read included an introduction in which Morrison writes: “Female freedom always means sexual freedom, even when—especially when—it is seen through the prism of economic freedom.” While I respect Morrison’s craft, I don’t personally agree with this framing. Throughout the book, the freest female characters are also the most sexually unrestrained, choosing partners without regard to consequences. For me, this reflects the central tensions I’ve often felt when reading Morrison’s work: I recognize the literary prowess but don’t agree with this belief. As someone who values intentionality in relationships and ethical sexuality, I believe there is freedom in discernment. My personal worldview differs from Morrison’s here, and I think that’s worth naming—especially since this quote helped me finally articulate why I sometimes feel at odds with what I’m “supposed” to take away from her narratives.

Of course, I also acknowledge that I am not Morrison’s intended audience. She has stated clearly that she writes for Black people—and I am a white woman. I honor that intention, while also appreciating the beauty, lyricism, and cultural specificity of this novel. Morrison evokes a place, a time, and a community with precision and poetry, showing rather than telling how racial injustice permeates generations.

For readers in recovery, or those who love someone with substance use disorder or alcohol use disorder, be advised that this book contains a disturbing scene involving the violent death of a character who struggles with addiction. A mother sets her son on fire, intentionally killing him because of his drug use. It’s a horrific and deeply stigmatizing portrayal. While I understand that literature doesn’t require characters to always make the “right” choices, scenes like this can be deeply harmful and may reinforce stigma around addiction. To anyone reading this who is struggling: You don’t deserve to die. You are not disposable. You can recover. We do recover. I acknowledge that the story is set in a time when resources for addiction recovery were nearly nonexistent, especially for a Black man. But violence is never the answer, and stories like this can perpetuate dangerous beliefs about addiction and worth.

With regards to diversity, the book explores colorism in the Black community, as well as racism faced by Black folks coming from immigrant white communities. It has multiple characters who fought in World War I who struggle with mental health afterwards. It also has a character who uses a wheelchair and is missing a limb. There is not any LGBTQIA+ representation that I noticed.

This is a novel that quietly devastates, not through high drama, but through its unflinching portrayal of how systemic racism, personal grief, and societal expectations shape lives over time. It’s beautifully written, deeply character-driven, and emotionally complex. Whether or not you’re part of Morrison’s intended audience, Sula is a compelling and powerful read. If you’re in recovery or close to someone who is, approach with care due to the painful and stigmatizing depiction of addiction. For those looking for fiction that treats mental health and recovery with care, check out my novel Waiting for Daybreak.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral or coupon codes, signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter, or tuning into my podcast. Thank you for your support!

3 out of 5 stars

Length: 174 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Get the Book Club Discussion Guide

A beautifully graphic designed 2 page PDF that contains: 1 icebreaker, 9 discussion questions arranged from least to most challenging, 1 wrap-up question, and 3 read-a-like book suggestions

View a list of all my Book Club Guides.

Two 1980s Horse Girl Books Face Off

Will The Horse that Came to Breakfast or Maggies Wish win?

I’m doing something a little bit different this week. I’ve been going through my bookshelves to determine what to keep and get rid of. If it’s a book I don’t really remember very well, I’m re-reading it to help decide. As a person born in the 1980s, I just so happened to have two middle grade horse girl books first published in the 1980s on the shelf. I didn’t remember anything about them. So I re-read both of them. Each re-read took about an hour. Let’s get into it.

First up we have The Horse that Came to Breakfast by Marilyn D. Anderson, first published in 1987. I picked this one up first because how could I not with that title? I was intrigued! The first sentence didn’t exactly draw me in because it referred to their home as a “house trailer.” I grew up with friends who lived in trailer parks, and my dad lived in one in the last few years of his life. I’ve never heard anyone call them a “house trailer.” The only thing I can think, based on the strong horse presence in the rest of the book, was the author mainly thought of horse trailers when she heard the word trailer and so thought she needed to differentiate. But really it’s the other way around. Trailer (where people live) and horse trailer (what you use to move horses).

Anyway, the basic plot of this book is that this little girl really wants a horse but her parents just got divorced, her dad is now completely out of the picture, her mom had to move them to a trailer, and money is very tight. But one day (in literally the first page of the book) a horse shows up in their yard. It’s a miracle! But her mom points out this horse must have an owner and makes her look for it. It turns out the horse is from a struggling horse riding instruction place. The little girl ends up collecting cans on the side of the road to pay for lessons on the horse. There’s a mean girl who shouldn’t get to ride the horse. The horse’s life is in danger. The little girl has to save him. Etc…

While I was skeptical of this book at first, it really did draw me in. In spite of certain aspects being dated (like how often this little girl was completely unsupervised and doing things like collecting cans along the side of the road or performing chores for random strangers she just met), the overall plot was thoughtful and heartwarming. There was no judgment of her mother for the divorce or the current financial situation, but it also empathically depicted how difficult it can be for kids to adjust to new life situations. It also highlighted caring for your neighbors and building a sense of community. Plus, there’s a happy ending for the girl and the horse. What more can you ask for?

Next up is Maggie’s Wish, first published in 1984. I’ll be honest. I didn’t notice until right now that the author is the same as for The Horse that Came to Breakfast! It felt like two totally different people wrote these books.

The basic plot of this one is that Maggie lives on a working farm with her mom and dad. She’s been asking for a pony to no avail. But one day her dad says the farm is getting something she’s going to really enjoy. She thinks it’s going to be a pony but it turns out to be two large draft horses for working the farm. The dad thinks this will be more fun than tractors. Maggie is disappointed but grows to love the draft horses only for her dad to sell them and ultimately buy her a pony.

The overall message of this book was bizarre. I’m still not sure what it was. Only when you learn to love the disappointing thing will you get what you really wanted? Don’t worry, when your father makes one poor financial decision he’ll continue to make them meaning you’ll ultimately get your pony one day? The family in this have a not great dynamic. The mother is kind of constantly making fun of the father. Of course, it’s a little hard to blame her for being frustrated when he really is making poor financial decisions with the family business without consulting her (his business partner) at all first. But those conversations should be had away from the daughter and not through passive-aggressive comments. I’m also having a hard time understanding how a farmer in 1984 could possibly think using two draft horses would be better than using a tractor. There’s also a scene where the dad spanks his daughter and her cousins (not his own kids) for running off unsupervised and almost getting hurt when he sends the dog to find them who then spooks a cow who almost runs them over. If you know you have a farm with cows who are spooked by dogs and you’re not sure where the children are, why would you send a dog after them? I understand spanking had a different cultural understanding in the 1980s but it’s hard to sympathize with the dad here when he was at least partially responsible for the whole near death experience.

The winner is…..

The Horse that Came to Breakfast! This is the one I decided to keep. Maggie’s Wish went to the local Little Free Library.

This is a great example of how one author can grow and change over time. Anderson’s characters acted with much more logic, even when making mistakes, in her later book. The overall plot was also more complex with elements I didn’t get into for the sake of space here. The message was clear and sound, backed up by memorable characters and intertwining plots. Maybe if the first book you pick up by an author is from early in their career, consider picking up one of the later books just to see.

Somewhat infuriatingly, I will note when I went to get the purchase links, Maggie’s Wish is available both digitally and as new printings. But The Horse that Came to Breakfast is only available as used vintage copies. Why? Why?

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral/coupon codes, or signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter. Thank you for your support!

Length The Horse that Came to Breakfast: 96 pages – novella/short nonfiction

Length Maggie’s Wish: 96 pages – novella/short nonfiction

Buy The Horse that Came to Breakfast (Amazon, not available on Bookshop.org)

Buy Maggie’s Wish (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Source: I’ve owned both books since childhood.

Book Review: The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty

The book that came before the classic horror movie featuring a little girl who may or may not be possessed by a demon and the priest struggling with his faith called upon to help her.

Summary:

Actress and divorced mother Chris MacNeil starts to experience ‘difficulties’ with her usually sweet-natured eleven-year-old daughter Regan. The child becomes afflicted by spasms, convulsions and unsettling amnesiac episodes; these abruptly worsen into violent fits of appalling foul-mouthed curses, accompanied by physical mutation. Medical science is baffled by Regan’s plight and, in her increasing despair, Chris turns to troubled priest and psychiatrist Damien Karras, who immediately recognises something profoundly malevolent in Regan’s distorted fetures and speech. On Karras’s recommendation, the Church summons Father Merrin, a specialist in the exorcism of demons . . .

Review:

I’d seen the classic horror movie and, while I thought certain shots were gorgeous and the soundtrack was beautiful, I felt rather ho-hum about the story overall. Imagine my surprise when I found the book version simultaneously thrilling and intellectually engaging. A difference even more interesting since Blatty wrote both. (It’s more common for a different author to write the screenplay adaptation of a book.)

From the beginning of the book, there are three story threads. First there’s Chris, the divorced, wealthy, actress mother who is an atheist and her daughter who starts acting funny. Second, there’s Father Karras, a psychiatrist and a priest who is having a crisis of faith. Third, there are recent desecrations in a local church that a detective is investigating. These three threads merge by the end of the book. But their separate developments kept me simultaneously intellectually engaged and thrilled.

While there absolutely is the thrilling aspect of what is wrong with Regan and can she be healed/saved from it, I was drawn in by the exploration of faith. How it presents in different people, even those we assume must have a very strong faith or none at all. What it means to have faith. How having faith impacts people. How evil forces can use someone’s doubts and misunderstandings against them. (This part of the book reminded me of a more subtle version of The Screwtape Letters.)

I really felt both for Father Karras and for Regan. For the former, I understood how adult life had slowly worn down his youthful faith. How it was easier for him to believe in things when he was young than it was now in middle-age. And I also felt for Regan, whose mother left her completely unequipped to protect herself against forces of darkness. The fact that her mother forbid the nanny to mention God to her but also simultaneously allowed her to play with a Ouija board. If she’s so atheist as to not want a child to even know the concept of God, shouldn’t she also ban all religious items, including ones used for witchcraft, from her home? I don’t view this as a writing flaw but rather an accurate assessment of how often atheism attacks the concept of God but not of other supernatural forces. Indeed, I think demonstrating this was probably a part of the point.

The book does a good job of leaving it up to the reader to decide if Regan was actually possessed by a demon or having a psychosomatic experience in response to the trauma from her parents’ divorce. I’m sure you can tell from my review that I fall on the she was possessed side. You can see from the book how much more traumatic the 1970s viewed divorce for children than we do now. The 1970s brought no-fault divorce, and so the divorce rate went up, but there was still social stigma. So even though for the modern reader a simple, relatively amicable divorce with a bit of an absent father is nowhere near enough trauma for a child to have a psychotic break, for the audience in the 1970s with the stigma still fresh, it was. And the scientific side of why they think this might be is well-explained. It’s just to me it’s very clear this is a demon.

My experience of the book being about faith matches what Blatty said in interviews in his life. It’s interesting how that has been overshadowed by the cultural experience of the movie as a horror classic. Perhaps the book can be both. Indeed, theological horror is a genre.

The reason it’s not a full five stars for me is I felt like the last third of the book wasn’t as strong as the first two-thirds.

Let me leave you with my favorite quote from the book.

I think the demon’s target is not the possessed; it is us … the observers … every person in this house. And I think—I think the point is to make us despair; to reject our own humanity, Damien: to see ourselves as ultimately bestial, vile and putrescent; without dignity; ugly; unworthy. And there lies the heart of it, perhaps: in unworthiness. For I think belief in God is not a matter of reason at all; I think it finally is a matter of love: of accepting the possibility that God could ever love us.

page 345

Overall, this is a complex book of theological horror. It keeps the plot moving forward with multiple threads and compelling scenes while also taking the time to contemplate big questions about faith. Well worth the read, even if you have seen the movie, as it is a different experience altogether.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral/coupon codes, or signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter. Thank you for your support!

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 403 pages – average but on the longer side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Get the Book Club Discussion Guide

A beautifully graphic designed 2 page PDF that contains: 1 icebreaker, 9 discussion questions arranged from least to most challenging, 1 wrap-up question, and 3 read-a-like book suggestions

View a list of all my Book Club Guides.

Why I Love Bridget Jones’s Diary & A Review of the 25th Anniversary Edition

A Delightful Start

My first encounter with Bridget Jones’s Diary was the 2001 movie starring Renee Zellweger, Hugh Grant, and Colin Firth. I remember stumbling onto it on my dad’s satellite tv when I was in high school. I’d long loved epistolary novels, but especially anything diary based. (The Dear America series was an early obsession.) Even in high school, I loved New Year’s Resolutions, and the idea of reinventing and improving myself. So those two incredible opening scenes of the movie when Bridget goes to a diastrous New Year’s Day turkey curry buffet and then subsequently decides to reinvent herself with New Year’s Resolutions and a diary to keep herself accountable drew me in immediately. From that point on, rewatching the movie became a holiday season/January tradition for me.

What’s This Diary About Anyway?

For those of you who don’t know, Bridget Jones’s Diary is a romcom told through Bridget’s diary entries for one full year. She’s a woman in her early 30s living in London and working in publishing. She spends the year initially falling for her boss at work, Daniel Cleaver, and later for Mark Darcy, a human rights barrister her mother tried to set her up with. Other key plot elements include the hang outs, trials, and travails of her friends (both singletons and marrieds), her mother and father’s late in life marriage troubles, and her ongoing quest for self-improvement, including struggles with alcohol, cigarettes, instants (the lottery), and delightful asides like why it takes her 3 hours to get ready in the morning.

Discovering the Book

A few years later, I finally picked up the book, and I was blown away. How could a movie I loved so much be even better in book form?! I could scarcely believe it. The audiobook version as read by Imogen Church is my go-to when I’m having trouble sleeping or am under a lot of stress and need to just relax for a bit. Her reading of Bridget is simply perfection.

Why Do I Love Bridget So Much, Exactly?

1. how each entry starts

At the start of each diary entry are some things that Bridget tracks. What exactly she’s tracking changes throughout the book. The key items are her weight, calories consume, alcohol drunk, cigarettes smoked, and instants (lottery tickets) bought. But there are other trackings that pop in like number of smoothies consumed or number of times called 1471 (like American *69 only it tells you what number called you rather than ringing them back). I love data and statistics and tracking the mundane things in my life. The lists at the start of each entry make me laugh because they remind me of myself, and they provide a different type of insight into Bridget. I also love how she self-comments on each item, especially how she will say “v.g.” for “very good.” This is one of those pop cultureisms that has made it into my own daily life.

2. depiction of diet culture

Sometimes I hear people talking about Bridget Jones (especially those who’ve only seen the movie), and they complain specifically about Bridget’s obsession with her weight when she is, in fact, a healthy weight. To them I say, that’s the point! This book is an amazing take-down of 1990s diet culture. Bridget is a healthy weight. But she doesn’t think she is. And anytime she’s having problems, she thinks they might be magically solved if she was “no longer fat.” In fact, in diary entries when Bridget is feeling particularly down are when she is most likely to berate herself for her size.

There are two episodes in the book that really drive home the fact that this is a critique of diet culture. The first is that Bridget does get down to her goal weight. She goes to a party with her friends and is ecstatic for them to see her. But they express concern. They don’t think she looks well. Her friend Tom tells her she looked better before. She has a bit of a breakthrough and wonders if her calorie counting is unhealthy and stops tracking them for a while. But then something stressful happens and she begins again. The second episode is when the same friend Tom wonders about how many calories are in something, and Bridget recites the precise number off to him. He’s shocked she knows this then proceeds to quiz her on the number of calories in various things, all of which she knows off the top of her head. She asks doesn’t everyone know this? To which Tom emphatically tells her know. Bridget briefly wonders what other information she could have stored in her head if it wasn’t so busy with calories. Amazing! Just because Bridget never breaks free of her disordered eating doesn’t mean the book itself isn’t criticizing the culture that inflicted it upon her to begin with.

3. Bridget is gloriously imperfect

At the beginning of the book Bridget drinks too much alcohol and smokes cigarettes. She struggles to get to anything on-time. One could say her doing things is always a series of unfortunate calamities. None of this really changes by the end of the year. One could argue that she kind of fails at the majority of her New Year’s Resolutions. But the thing that does change is that Bridget has started to like the core of who she is, and that in turn has made it possible for her to open up to a kind man, instead of, as she would say, the fuckwits she’s been dating previously. She’s become a bit kinder to herself about the flaws that aren’t really flaws per se but just personality quirks (like her complete inability to do anything efficiently). But she’s also very willing to keep trying on the things she probably should still be improving on (like the number of cigarettes she smokes). She simply feels real.

4. it’s hysterically funny

Part of what makes the book funny is, due to its diary entry nature, not every single scene necessarily contributes to the main plot, although each one does help with character development. As such, we get some scenes that are just simply bananas hysterical that a book with a different structure might have left out. One of my favorites is when Bridget decides to study herself to see why it takes her so long to get out the door in the morning. We then get time-stamped entries of each activity she does. It’s gloriously inefficient (including imagining her taking the time to actually write all of this down when she’s already running late to work…but she does it anyway.) Even secondary characters are richly imagined, which I think is probably partially due to the fact that Helen Fielding based many of them on people in her real life (she discusses this in the special 25th anniversary edition). Everyone in Bridget’s world, even her over-the-top batshit mother, feels real. And that’s part of what makes it so funny. It’s easy to imagine all of this really happening.

Review of the 25th Anniversary Edition

For my birthday this year, my husband gifted me the 25th anniversary edition of Bridget Jones. It’s a beautiful hardcover with a foil embossing of Bridget’s famous granny panties on the cover. Even more exciting, it has over 100 pages of new and unpublished material from Helen Fielding.

The first section is “Life Before Bridget” which gives a selection of some of Helen’s journalism articles from before Bridget took off. (Bridget was originally a newspaper column before becoming a book). I loved seeing Helen’s development as a writer and especially the context she gave. My favorite was a restaurant review in which she explains she went with her two best friends who were the inspiration for Jude and Shazzer in the book. I could hear echoes of those two in the restaurant review and absolutely loved it.

The second section is “The Diary of Bridget Jones” in which she explains how the idea for Bridget came to be, and we get selections from some of the initial Bridget newspaper articles.

Next is “Bridget Becomes a Thing,” which includes her interview with Colin Firth in character as Bridget, comics from the time period that reference Bridget, and Helen’s reflections on how it felt to realize she had written a cultural touchstone.

The next section is “Bridget in the 21st Century,” which are Bridget diary entries from 2018 on that Helen wrote for a variety of reasons from inclusion in a feminism book to addressing Brexit to the whole…2020 thing.

There is also an Introduction and a Conclusion written in Helen’s voice but int he style of a Bridget diary entry.

I had to stop saying “I loved it” after the end of each section explanation. It was getting ridiculously repetitive. It’s so rare for me to get to know an author better and enjoy their work more as a result. In all honesty I usually try to avoid getting to know an author because I don’t want things ruined for me. This had the opposite effect on me. I could see being friends with Helen. She’s witty and down-to-earth. I especially liked one section where she talked about people asking her about why she wrote something so silly and why she didn’t write more serious things and how her response was her first book was very serious (set in a war zone or something, I don’t remember), and no one wanted to read it. But they did want to read this. And that’s just the sort of smart commentary that’s throughout the book too. Posh people can try to judge Bridget for how she is, but how she is is, in fact, at least partially a survival response to how the world is. She’s doing her best in a good-natured sort of way in a world that seems to constantly harshly critique her no matter what.

It’s probably obvious by now this is 5 out of 5 stars from me.

Buy the 25th Anniversary Edition (Amazon not available on Bookshop.org)

Buy the Audiobook Read by Imogen Church (Amazon not available on Bookshop.org)

Buy the Movie (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Length: 464 pages (25th anniversary edition) – chunkster

310 pages (original content) – average but on the longer side

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

Book Review: Jaws by Peter Benchley

Get ready for shark week with this 1970s classic!

Summary:

A great white shark starts terrorizing a coastal town just as the money-making summer season begins. The classic, blockbuster thriller of man-eating terror that inspired the Steven Spielberg movie and made millions of beachgoers afraid to go into the water. Experience the thrill of helpless horror again—or for the first time!

Review:

As a New England girl born and raised, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve watched Jaws the movie. Everything about it is just so *chef’s kiss* perfectly small New England beach town. (The movie is set on Long Island, New York, but was filmed on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, and, let me tell you, everything about it reads New England to me.) Plus, my cat absolutely adores watching Jaws. She’s obsessed with that shark. With summer rolling around once again, I decided it was high time I read the book. The book is almost always better than the movie, right? Well, in this case, that almost really comes into play. (Spoilers ahead for both the movie and the book. If you haven’t seen this classic yet, please go watch it then come back to the book review.)

The book starts off strong with a close omniscient perspective of the shark getting ready to eat the drunk lady swimming in the ocean. The book could easily sway into anthropomorphizing territory, imagining the viciousness of the shark. But it consistently describes a creature whose instinct is to feed. What, exactly, made it come in to Amity and stick around is a mystery that is never solved. This first scene is one of the strongest in the book. But I have to admit I was hearing the absolutely classic movie soundtrack in my head while I was reading it, and we all know how essential that is at building suspense. So I’m not sure it’s safe to say I felt engaged purely because of the book.

But it didn’t take too long for the book to showcase itself as…worse than the movie. When we meet Sheriff Brody, he mentions a problem they had the previous summer where a Black gardener sexually assaulted six white women, none of whom would press charges. The only point of this from a narrative perspective is to demonstrate how the police department will keep things under wraps in order to protect the summer season. But it’s a hatefully racist way to establish this, narratively. Even if I charitably imagine that this is supposed to be pointing out the racial divide in Amity that is later even clearer in the book, there are better ways to do that than to play into this horribly racist myth of the serial Black assaulter of white women.

There are two other plot points in the book that weren’t in the movie at all. First, there’s that Brody’s wife cheats on him with Hooper because she feels some weird Feminine Mystique style ennui about her life as a housewife at a lower social class than she was before she got married. (We only see the sex in flashbacks she has about it and how strange and scary Hooper was). There is a large scene where she has lunch with Hooper first and talks about her sexual fantasies. Kind of slows down the pace of the suspense from the shark attacks.

The other additional plot point is that the mayor of the town is mixed up with the mafia because he had to take out a loan from a loan shark (har har) to pay his wife’s cancer treatment medical bills. (What on earth do other countries with nationalized health care do to justify characters taking out unwise loans? This is such a common plot device…but I digress.) The mafia wants the beaches to be kept open. This is a big motivator for why the mayor keeps insisting on it. But I don’t think this motivator is necessary. The economic pressure and need of a tourist town to keep their main tourist attraction open is more than enough motivation. Anyone who has any familiarity with a town that depends on seasonal tourism gets that. Spielberg was right to cut this from the movie. This also brings about a scene I found much more disturbing than any shark attack, which is that the mafia kills Brody’s son’s cat in front of his son, and then Brody takes the dead cat and throws it in the mayor’s face.

The final act where Quint, the old-time fisherman, takes Brody and Hooper out on his boat to hunt the shark is overall pretty good. There’s some nice tension between the three of them, and Quint really has to eat his words about the shark not being intelligent. It does not end with the 70s style bang of the movie. But I kind of liked the simplicity of the ending, leaving Brody to swim to shore and deal with the aftermath on his own without any reader audience.

I’ve seen some lists of the differences between the book and the movie with mistakes and inaccuracies on them, so I do want to clear up a couple of things. Brody is afraid of the water in the book. This is well-established; I’m not sure how people missed that. Mrs. Kintner does slap Brody in the book when she confronts him about the shark killing her son.

The version of the book I read also had an introduction by the author where we find out that he was, basically, a “summer person” himself – from a wealthy family and a legacy graduate of Harvard (his father also went to Harvard). His father was a novelist, and because of that connection, Benchley got an agent before he even had a book written. By Benchley’s own recollection, he sold the idea for Jaws and then they told him he needed to write the book, and the screenplay was sold before the book was even written. He took a first shot at the script, and Spielberg told him to throw out a lot of the stuff that I mentioned in my review as things I didn’t like. Moral of the story being privileged dude sold an admittedly solid idea based on the idea alone to someone else who directed it into it being a classic.

Overall, it was interesting to read the book behind the movie, but I also now have the perfect answer for the next time someone asks me, “When is the movie ever better than the book?”

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

3 out of 5 stars

Length: 320 pages – average but on the longer side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Get the Book Club Discussion Guide

A beautifully graphic designed 2 page PDF that contains: 1 icebreaker, 9 discussion questions arranged from least to most challenging, 1 wrap-up question, and 3 read-a-like book suggestions

View a list of all my Book Club Guides.

Book Review: Coffee Will Make You Black by April Sinclair (Series, #1)

Summary:

Set on Chicago’s Southside in the mid-to-late 60s, following Jean “Stevie” Stevenson, a young Black woman growing up through the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. Stevie longs to fit in with the cool crowd. Fighting her mother every step of the way, she begins to experiment with talkin’ trash, “kicking butt,” and boys. With the assassination of Dr. King she gains a new political awareness, which makes her decide to wear her hair in a ‘fro instead of straightened, to refuse to use skin bleach, and to confront prejudice. She also finds herself questioning her sexuality. As readers follow Stevie’s at times harrowing, at times hilarious story, they will learn what it was like to be Black before Black was beautiful.

Review:

After reading Tales of the City by Armistead Maupin (review) and finding myself disappointed with how it handled race, I intentionally looked for older classics of LGBTQIA+ lit written by Black authors. (As a starting place. I intend to continue this searching with other BIPOC groups). In my search I found this book listed as an own voices depiction of a queer young Black woman in the South Side of Chicago. My library had a digital copy, so I was off.

First published in 1995, this is certainly an own voices book. The author grew up in Chicago in the same time period as Stevie, and that authenticity really shines through. The book is divided into three parts. Part 1 (spring 1965 to summer 1967), Part 2 (fall 1967 to fall 1968), and Part 3 (fall 1969 to spring 1970). Part 1 begins in Stevie’s last year of middle school. It establishes the systemic racism Stevie and her family live with that the Civil Rights movement that Stevie will later become involved in in high school. It also demonstrates Stevie’s difficult relationship with her mother. In Part 2, Stevie enters high school, Dr. King is assassinated, and Stevie starts to push back on racism and colorism. In Part 3, Stevie starts to question her sexuality and also the lack of interracial friendships and relationships she sees among her friends and family.

In some ways this was a tough book to read. It pulls no punches about what life was like for a young Black girl at this time. Although it always pains me to read about racism and colorism, there was an extra twinge in reading this because Stevie is just such an immediately likable little girl with a protective mother. The book opens with Stevie asking her mother what a virgin is (because a boy at school asked her if she was one), and her mother not wanting to tell her. This reminded me of all the conversations about Black girls being forced to grow up too fast and letting them stay the little girls they are. Although I advocate for frank talks about sexuality with questioning children, I also understood her mother’s impulse to keep Stevie little just a while longer.

Stevie’s sexuality is left open-ended in this book, in spite of my finding it on a list of lesbian fiction originally. Essentially the idea is posited that sometimes adolescents feel confused only to realize later they’re straight. I wondered if this is what happens with Stevie so peaked at the sequel. (spoiler warning!) Apparently in the sequel Stevie identifies as bisexual. This thrilled me, because there’s so little representation of bisexual folks in literature, but also because I felt a bit of a twinge of recognition when reading about Stevie’s confusion in the book. Part of why she’s so confused about if she’s straight or a lesbian is because the answer is neither. It was a great depiction.

I did feel the book ended kind of abruptly. It’s definitely a bit of a plot hanger that leaves you yearning for the sequel. Not in an uncomfortable way but more in a I want to see Stevie finish growing up way. Plus, it’s the start of the 1970s, and that’s such a fun time period to read about.

Overall, this own voices book gives a realistic yet fun depiction of growing up Black in the South Side of Chicago in the 1960s. If you’re coming for the queer content, hang in there, it shows up in Part 3. A great way to diversify your reading.

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 256 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Get the Reading Group / Book Club Discussion Guide

A beautifully graphic designed 2 page PDF that contains: 1 icebreaker, 9 discussion questions arranged from least to most challenging, 1 wrap-up question, and 3 read-a-like book suggestions

View a list of all my Discussion Guides.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

Book Review: Tales of the City by Armistead Maupin (Series, #1)

Summary:

San Francisco, 1976. A naïve young secretary, fresh out of Cleveland, tumbles headlong into a brave new world of laundromat Lotharios, pot-growing landladies, cut throat debutantes, and Jockey Shorts dance contests. The saga that ensues is manic, romantic, tawdry, touching, and outrageous

Review:

This was first published as a novel in 1978, although it was published prior to that as a serialized story in a San Francisco newspaper. It is considered a classic of LGBTQIA+ literature. The first tv show miniseries based upon it that premiered in 1994 had a same-sex kiss made history and was also protested (source). The Netflix reboot/update in 2019 brought fresh attention to it, and I thought it was high-time I read the classic.

It’s clear that some restraints were placed upon Maupin, either by the newspaper or simply the culture of the time. Our window into the queer world in San Francisco is given to us by Mary Ann Singleton – a single cis straight woman who comes from Cleveland for a visit and decides to stay. She’s invited into Barbary Lane and declared one of us, although why exactly she’s considered part of the found family is not resolved in the first book.

The book is definitely a product of the 1970s. 1970s fashion and freewheeling culture are everywhere. Lack of acceptance of queer people is a real threat and concern, and the AIDS crisis had not yet hit. It’s an interesting snapshot of a very particular point in time.

While characters are quite loose about who they will sleep with, there’s also a lack of diversity in the cast of main characters that’s jarring. Especially for a story set in a city that’s so diverse. Particularly noticeable to me was how the Asian-American characters are all peripheral, even with this being San Francisco. I don’t think this lack of diversity is a product of its time – there were other very forward-thinking works of fiction at the same time as this. This lack of diversity is something to keep in mind when approaching the book.

There are also two plot twists that revolve around race, and I don’t think either is handled with particular grace. The race of someone’s lover is identified by pointing to a yellow flower. This is obviously offensive. While it seems to me that the character who does this is someone we’re supposed to think badly of, on the other hand, it seemed to me that this was supposed to be a funny moment. And it definitely was not. In the other case, a character reveals that they believe that the only way to become a successful model is to be Black. It is unclear what the other character they are speaking to thinks of that. I think this instance may be intentionally leaving it up to the reader to decide what they think, but it’s also a strange plot point in a book that’s mostly about hookups and very little about careers.

This reminded me very much of other books and tv shows that have dramatic, gasp-inducing storylines with large casts of characters whose lives intertwine and overlap in mysterious ways. Think Jane the Virgin or Desperate Housewives just with fewer identical twins and less murder (so far…..) and more queer characters. If you like that type of storytelling, then you’ll likely find this hilarious and engaging. If you don’t, then you probably won’t.

I personally found it to be a rapid read with an engaging storyline and funny chapter titles. I wished it had been more forward-thinking and intersectional, but I also respect that the mere depiction of queer people in a soap opera like story was quite groundbreaking. I appreciate it for what it is, and it was a fun, quick read.

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 386 pages – average but on the longer side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Get the Reading Group / Book Club Discussion Guide

A beautifully graphic designed 2 page PDF that contains: 1 icebreaker, 9 discussion questions arranged from least to most challenging, 1 wrap-up question, and 3 read-a-like book suggestions

View a list of all my Discussion Guides.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

Book Review: We by Yevgeny Zamyatin

Summary:

In a glass-enclosed city of perfectly straight lines, ruled over by an all-powerful “Benefactor,” the citizens of the totalitarian society of OneState are regulated by spies and secret police; wear identical clothing; and are distinguished only by a number assigned to them at birth. That is, until D-503, a mathematician who dreams in numbers, makes a discovery: he has an individual soul. He can feel things. He can fall in love. And, in doing so, he begins to dangerously veer from the norms of his society, becoming embroiled in a plot to destroy OneState and liberate the city.

Set in the twenty-sixth century AD, We was the forerunner of canonical works from George Orwell and Alduous Huxley, among others. It was suppressed for more than sixty years in Russia and remains a resounding cry for individual freedom, as well as a powerful, exciting, and vivid work of science fiction that still feels relevant today. Bela Shayevich’s bold new translation breathes new life into Yevgeny Zamyatin’s seminal work and refreshes it for our current era.

Review:

The history of this book is fascinating. Smuggled out of Soviet Russia and only ever published in translation in exile from Russia. Published before 1984 and Brave New World and said to have been at least some level of influence on both. So it’s absolutely an important read from the perspective of scifi history.

A what-if version of automation and industrialization. These successes have led to a society where humans no longer have mothers, fathers, or even real names. Instead they have numbers. D-503 is our narrator. He’s designing a rocket ship for the space program. He falls in with I-330, a woman working with a kind of back to nature resistance.

I’m not sure I liked either society depicted. It kind of reminded me of one of the societies depicted in The Time Machine that I didn’t like all that much either. But I was definitely moved and engaged and wanted to find out what happened. (The ending is bleak. I’m not sure why I hoped for anything else!)

One thing that made this a challenging read is that D-503 refers to I-330 as I. This made some sentences confusing since it’s also narrated in the first person from his point of view. It was not unusual for me to have to re-start a sentence after realizing it was actually about I-330 and not D-503 or vice versa. It’s unclear to me how much of this is a translation choice and how much of it is authentic to the book as originally written in Russian.

Another thing that rubbed me the wrong way is how the Black character is described. There’s a large, recurring focus on the size of his lips. On the one hand, the depiction of this character is very open-minded and equal. He and D-503 are both sort of married to the same woman, know it, and all consider themselves friends. But, on the other hand, the focus on his lips repeatedly was jarring. I’m again, not sure if this was in the original Russian or an awkward translation.

A creative world building element that I enjoyed is how this totalitarian regime keeps watch on its citizens. This was written before much technology, and so the citizens all live in glass homes. They have to get a special ticket to be able to pull the blinds. These are only issued for sanctioned sexual encounters. Thus to have private meetings, you must get tickets to have sexual relations with the person you want to meet with.

Recommended to those with an interest in the trajectory of scifi dystopias over time or with an interest in Russian literature.

3 out of 5 stars

Length: 256 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: NetGalley

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

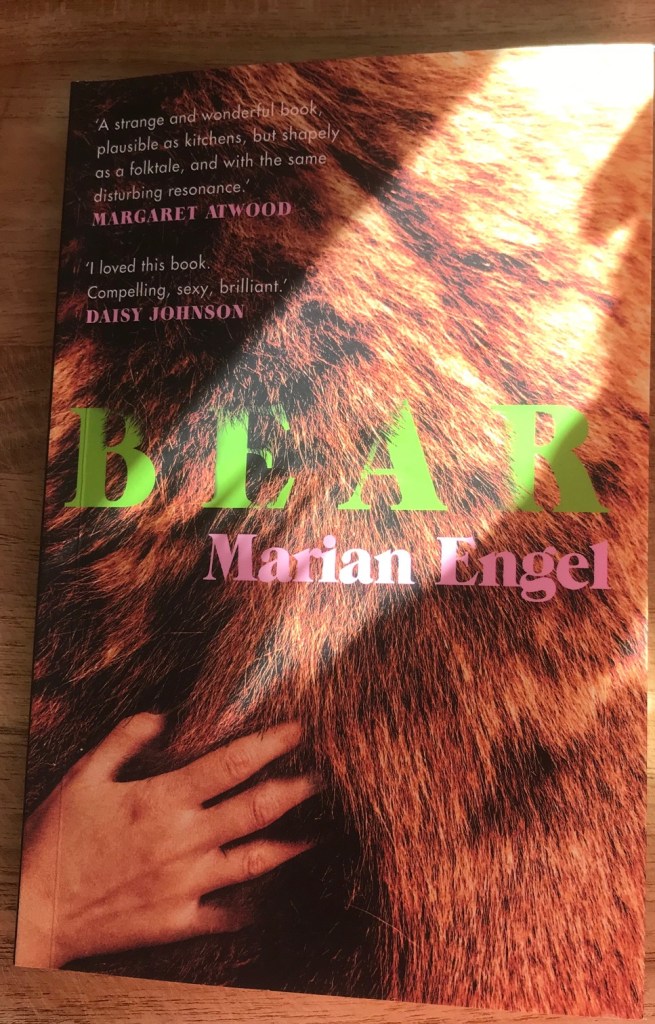

Book Review: Bear by Marian Engel

Summary:

A librarian named Lou is called to a remote Canadian island to inventory the estate of a secretive Colonel whose most surprising secret is a bear who keeps her company–shocking company.

Review:

I don’t recall anymore how I heard about this book, but this is what I heard about it:

There’s this book that’s considered a Canadian classic where a librarian has sex with a bear.

Ok. I was left with questions. First, this sounds like erotica – how is it a classic? Second, as a trained librarian I immediately wondered if the librarian part was essential to the story. Third, does she really have sex with a bear? Then I became even more intrigued when I discovered I couldn’t get this book digitally but only in print AND it’s out of print in the US so it’s far cheaper to purchase it abroad and have it sent here. So, now that I got this book from the UK and read it (in one weekend), let me answer these questions for you.

First, I wouldn’t call this erotica. The point, in spite of the murmurings about it, is absolutely not about sex with a bear, whereas in erotica, the point is the sex. I in all honesty would say this is a book about burnout. Lou is an archivist who is in a rut. When the nameless Institute she works for sends her to this estate that has been left to them to inventory their materials, her time in nature and her experiences with the locals (yes, including Bear), reveals her massive burnout to her.

She wondered by what right she was there, and why she did what she did for a living. And who she was.

(pg 93)

Second, I would definitely say the librarian part is essential to the story. Librarianship is a feminized profession. This book was first published in 1976. It is an exploration of what it means to be a working woman and how the world views working women, even when our work is performed outside of the public’s eye (perhaps especially when our work is performed outside of the public’s eye). I also thought this book does an excellent job of showing how even though librarianship is a feminized profession, those in the positions of greatest power within libraries and archives are men. Lou’s boss is a man, and this is relevant to her negative work experience.

Third, does she actually have sex with a bear? Ok, slight spoiler warning here. There is no penetration. She tricks the bear to go down on her. That’s it. I didn’t find it particularly shocking, but I’m a millennial from the internet generation that grew up with the internet urban legend about the woman with the dog and the peanut butter so. I viewed the transgressive act with Bear as serving two purposes. First, Lou has a tendency toward self-sabotage, self-loathing, and self-punishment. I think transgressing in this way makes her see how she’s transgressing against herself and her own soul in other ways and makes her refind her own sense of self. Second, I think it’s important to note that at the beginning of the book an Indigenous woman named Lucy kind of hands off the caretaking of Bear to Lou. At the end of the book, she hands the caretaking back to Lucy. I view this as an acknowledgement that just because you can do something doesn’t mean you should. It doesn’t mean it’s your life calling. There are other interesting takes on this as a commentary on colonialism, which I also think are valid.

So do I see why this is a Canadian classic? Yes, absolutely. The whole story oozes Canada from the juxtaposition of the wilderness with the city to the entwining of European and local history to the acknowledgment of the realness and relevance of local Indigenous peoples. (These peoples are not of the past but are of the present, something I think Canadian literature often does a better job with than US literature).

I thought I was going to read this book and laugh at it, kind of like how folks on book-tok are laughing about the ice planet barbarians right now. Instead, I found a unique story about a woman’s time in the semi-wilderness and how it makes her confront her burnout and how her career is a poor fit for her. How her life setup is causing her to transgress and how that needs to change. A shocking way to get the point across? Perhaps. But an important point nonetheless.

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 167 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: Purchased

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Get the Reading Group / Book Club Discussion Guide

A beautifully graphic designed 2 page PDF that contains: 1 icebreaker, 9 discussion questions arranged from least to most challenging, 1 wrap-up question, 3 read-a-like book suggestions

View a list of all my Discussion Guides.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!