Archive

Book Review: Sula by Toni Morrison

A lyrical and haunting novel about two Black women whose lifelong friendship is tested by betrayal, love, and the weight of their small-town community’s judgment.

Summary:

Sula and Nel are two young black girls: clever and poor. They grow up together sharing their secrets, dreams and happiness. Then Sula breaks free from their small-town community in the uplands of Ohio to roam the cities of America. When she returns ten years later much has changed. Including Nel, who now has a husband and three children. The friendship between the two women becomes strained and the whole town grows wary as Sula continues in her wayward, vagabond and uncompromising ways.

Review:

This was my second Toni Morrison novel—the first being The Bluest Eye, which I read back in college. Morrison’s prose is deeply lyrical, which makes her books swift reads on the surface, even when they delve into painful and challenging themes. Sula is no exception.

Each chapter is titled with the year it takes place in, but only covers a brief vignette from that year. Despite spanning several decades, this is a short novel, structurally and in page count. Though the title suggests a singular character focus, Sula is as much about a place—the Bottom, a Black neighborhood in a Southern state situated on the hillside, land the white residents had no interest in. The reason for its ironic name is revealed in the first chapter through a racist tale, setting the tone for the book’s critique of systemic racism.

Indeed, one of the novel’s most striking accomplishments is how clearly it shows that systemic racism ruins lives, whether characters comply with social expectations or resist them. For me, Nel represents compliance while Sula represents defiance—yet neither of them leads a life free from pain. Every person in their orbit suffers in some way, and that suffering is deeply entangled with the racist systems surrounding them.

The edition I read included an introduction in which Morrison writes: “Female freedom always means sexual freedom, even when—especially when—it is seen through the prism of economic freedom.” While I respect Morrison’s craft, I don’t personally agree with this framing. Throughout the book, the freest female characters are also the most sexually unrestrained, choosing partners without regard to consequences. For me, this reflects the central tensions I’ve often felt when reading Morrison’s work: I recognize the literary prowess but don’t agree with this belief. As someone who values intentionality in relationships and ethical sexuality, I believe there is freedom in discernment. My personal worldview differs from Morrison’s here, and I think that’s worth naming—especially since this quote helped me finally articulate why I sometimes feel at odds with what I’m “supposed” to take away from her narratives.

Of course, I also acknowledge that I am not Morrison’s intended audience. She has stated clearly that she writes for Black people—and I am a white woman. I honor that intention, while also appreciating the beauty, lyricism, and cultural specificity of this novel. Morrison evokes a place, a time, and a community with precision and poetry, showing rather than telling how racial injustice permeates generations.

For readers in recovery, or those who love someone with substance use disorder or alcohol use disorder, be advised that this book contains a disturbing scene involving the violent death of a character who struggles with addiction. A mother sets her son on fire, intentionally killing him because of his drug use. It’s a horrific and deeply stigmatizing portrayal. While I understand that literature doesn’t require characters to always make the “right” choices, scenes like this can be deeply harmful and may reinforce stigma around addiction. To anyone reading this who is struggling: You don’t deserve to die. You are not disposable. You can recover. We do recover. I acknowledge that the story is set in a time when resources for addiction recovery were nearly nonexistent, especially for a Black man. But violence is never the answer, and stories like this can perpetuate dangerous beliefs about addiction and worth.

With regards to diversity, the book explores colorism in the Black community, as well as racism faced by Black folks coming from immigrant white communities. It has multiple characters who fought in World War I who struggle with mental health afterwards. It also has a character who uses a wheelchair and is missing a limb. There is not any LGBTQIA+ representation that I noticed.

This is a novel that quietly devastates, not through high drama, but through its unflinching portrayal of how systemic racism, personal grief, and societal expectations shape lives over time. It’s beautifully written, deeply character-driven, and emotionally complex. Whether or not you’re part of Morrison’s intended audience, Sula is a compelling and powerful read. If you’re in recovery or close to someone who is, approach with care due to the painful and stigmatizing depiction of addiction. For those looking for fiction that treats mental health and recovery with care, check out my novel Waiting for Daybreak.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral or coupon codes, signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter, or tuning into my podcast. Thank you for your support!

3 out of 5 stars

Length: 174 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Get the Book Club Discussion Guide

A beautifully graphic designed 2 page PDF that contains: 1 icebreaker, 9 discussion questions arranged from least to most challenging, 1 wrap-up question, and 3 read-a-like book suggestions

View a list of all my Book Club Guides.

Book Review: Witchcraft for Wayward Girls by Grady Hendrix

A chilling blend of historical fiction and supernatural horror, this novel explores what happens when pregnant teenage girls—hidden away in a 1970s home for wayward girls—discover the dark power of witchcraft.

Summary:

They call them wayward girls. Loose girls. Girls who grew up too fast. And they’re sent to the Wellwood Home in St. Augustine, Florida, where unwed mothers are hidden by their families to have their babies in secret, give them up for adoption, and most important of all, to forget any of it ever happened.

Fifteen-year-old Fern arrives at the home in the sweltering summer of 1970, pregnant, terrified and alone. Under the watchful eye of the stern Miss Wellwood, she meets a dozen other girls in the same predicament. There’s Rose, a hippie who insists she’s going to find a way to keep her baby and escape to a commune. And Zinnia, a budding musician who knows she’s going to go home and marry her baby’s father. And Holly, a wisp of a girl, barely fourteen, mute and pregnant by no-one-knows-who.

Everything the girls eat, every moment of their waking day, and everything they’re allowed to talk about is strictly controlled by adults who claim they know what’s best for them. Then Fern meets a librarian who gives her an occult book about witchcraft, and power is in the hands of the girls for the first time in their lives. But power can destroy as easily as it creates, and it’s never given freely. There’s always a price to be paid…and it’s usually paid in blood.

Review:

I had previously read Grady Hendrix’s My Best Friend’s Exorcism and remembered liking it more than I actually did. When I revisited my review, I realized I had enjoyed the concept far more than the execution—and unfortunately, that’s exactly how I feel about this book as well.

One thing I didn’t realize before picking this up is that Hendrix is a male author. I read My Best Friend’s Exorcism digitally, so it wasn’t until I saw the author photo on my library copy that it became obvious. Now, that’s not to say men can’t or shouldn’t write about women’s issues—but in my experience, if a book is expressly about women’s experiences (such as pregnancy and abortion), I tend to dislike it when it’s written by a man. Hendrix acknowledges this in a note, explaining that his inspiration came from a family member’s experience as a wayward girl, and I appreciate the personal connection as well as the research he put in. That said, I still struggled with the execution. In retrospect, this also explains issues I had with My Best Friend’s Exorcism—especially the queer-baiting between the two best friends. The way their relationship was written didn’t quite reflect how best girlfriends interact. I now wonder if Hendrix was inserting subtext without realizing it. But I digress—back to this book.

This is a long book, and it takes quite a while before the supernatural horror elements appear. When they do, they feel sporadic—as if the book can’t quite decide whether it wants to be historical fiction or horror. According to the author’s note, an earlier version was pure historical fiction, and it shows. The witchcraft elements feel both tacked-on and underwhelming, lacking the impact they seem to be aiming for. The spellcasting scenes, in particular, drag on too long—the book repeatedly emphasizes how rituals are tedious, repetitive, and boring, and then actually makes the reader sit through them in full dialogue.

The novel also struggles with whether the witches are heroes or villains. At first, they seem to empower the girls in a feminist, girl-power way, but later, they’re positioned as the main threat. I can see the poetic logic in showing that these girls had no real options, but at the same time, a novel like this needs a stronger thematic core—a sense of hope, justice, or at least a clear vision for a better future. On the plus side, I never knew what would happen next or how it would wrap up. Even when I felt frustrated, I kept reading simply because I needed to know how it all ended.

While the book does include a Black teen girl at the home, the handling of race and racism felt superficial at best. The only acknowledgment of racism in 1970s Florida is a scene where the home’s director initially wants to separate the Black girl from the others, only for a hippie character to protest and swap rooms with her. That’s it. This felt wildly unrealistic for the time period.

Beyond this, there are three other Black characters: the cook, the maid (her sister), and a driver. While these are historically accurate roles, the cook is a blatant magical negro trope, complete with a sassy personality and a role that exists entirely to serve and clean up after the white girls. I cringed. A lot. The white characters take advantage of her kindness without any acknowledgment of how their actions impact her life. I also disliked how Black characters’ skin tones were described.

Readers should be aware that this book includes:

- Graphic descriptions of self-injury related to spellcasting.

- Traumatic childbirth.

- Forced institutionalization & adoption.

- Emotional abuse.

- Mentions of CSA & child abuse (off-page).

- A spellcasting scene with explicit Christian blasphemy. (Expected for witches, but I do think it could have achieved the same effect without spelling out the blasphemy.)

Ultimately, this is historical fiction with horror elements rather than a true horror novel. It would have benefited from stronger thematic direction and a more nuanced approach to diversity, avoiding the Magical Negro trope. The book understands that these wayward homes were a problem, but it doesn’t seem to take a stance on what should have been done differently. It sends mixed messages about abortion, single teen motherhood, and autonomy—leaving it feeling murky rather than impactful. Recommended for readers who enjoy historical fiction with a touch of horror—and who don’t mind waiting for the horror to arrive. For those interested in the real history behind these homes, The Girls Who Went Away is a must-read.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral/coupon codes, or signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter. Thank you for your support!

3 out of 5 stars

Length: 482 pages – chunkster

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Book Review: The Cuban Heiress by Chanel Cleeton

Two women aren’t exactly what they appear to be on a cruise from NYC to Cuba in 1936.

Summary:

In 1934, a luxury cruise becomes a fight for survival as two women’s pasts collide on a round-trip voyage from New York to Havana in New York Times bestselling author Chanel Cleeton’s page-turning new novel inspired by the true story of the SS Morro Castle.

New York heiress Catherine Dohan seemingly has it all. There’s only one problem. It’s a lie. As soon as the Morro Castle leaves port, Catherine’s past returns with a vengeance and threatens her life. Joining forces with a charismatic jewel thief, Catherine must discover who wants her dead—and why.

Elena Palacio is a dead woman. Or so everyone thinks. After a devastating betrayal left her penniless and on the run, Elena’s journey on the Morro Castle is her last hope. Steeped in secrecy and a burning desire for revenge, her return to Havana is a chance to right the wrong that has been done to her—and her prey is on the ship.

As danger swirls aboard the Morro Castle and their fates intertwine, Elena and Catherine must risk everything to see justice served once and for all.

Review:

A delightful and unique mystery set in 1936 against the backdrop of the actual SS Morro Castle whose last cruise ended in tragedy.

The mystery is told in alternating pov’s of Catherine and Elena. I liked both women, and so enjoyed both pov’s. Elena is Cuban, and Catherine (“Katie”) is Irish-American. We know right from the beginning that Catherine isn’t the heiress she’s pretending to be, and that the world thinks Elena is dead when she really isn’t. What we don’t know is precisely why. Catherine seems at first to be running some sort of scam, and she’s an engaging and likeable scam artist. Elena is more of the strong and silent type, and it at first seems like she might be working on something tied to smuggling from Cuba. But it is clear that whatever she is doing has some non-self-centered motivation. Both characters are well-done and each get their own romances, although Catherine’s is much more fleshed-out. (This is a closed door romance.)

The time period is reflected in the settings and dialogue without overshadowing the main mystery. The mystery itself is really only a mystery because key pieces of information are withheld from the reader. That’s my least favorite type of mystery, so I was a bit annoyed by that. Since the boat is only docked for one day in Havana, we don’t get to see much of Cuba, and I would have liked to have seen more. Perhaps in a flashback, since Elena is originally from Cuba.

Overall, this is an enjoyable historic mystery with a dash of romance in a luxury setting of a 1936 cruise ship that still manages to make both of its main characters relatable and likeable. Recommended for those who like historic mysteries and romance.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral/coupon codes, or signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter. Thank you for your support!

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 336 pages – average but on the longer side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Book Review: The Foundling by Ann Leary

It’s 1927, and eighteen-year-old Mary Engle thinks she’s found her way to independence and success when she starts working as a secretary for a woman doctor at a remote institute for mentally disabled women. But not everything is as it appears to be at Nettleton State.

Summary:

It’s 1927 and eighteen-year-old Mary Engle is hired to work as a secretary at a remote but scenic institution for mentally disabled women called the Nettleton State Village for Feebleminded Women of Childbearing Age. She’s immediately in awe of her employer—brilliant, genteel Dr. Agnes Vogel.

Dr. Vogel had been the only woman in her class in medical school. As a young psychiatrist she was an outspoken crusader for women’s suffrage. Now, at age forty, Dr. Vogel runs one of the largest and most self-sufficient public asylums for women in the country. Mary deeply admires how dedicated the doctor is to the poor and vulnerable women under her care.

Soon after she’s hired, Mary learns that a girl from her childhood orphanage is one of the inmates. Mary remembers Lillian as a beautiful free spirit with a sometimes-tempestuous side. Could she be mentally disabled? When Lillian begs Mary to help her escape, alleging the asylum is not what it seems, Mary is faced with a terrible choice. Should she trust her troubled friend with whom she shares a dark childhood secret? Mary’s decision triggers a hair-raising sequence of events with life-altering consequences for all.

Review:

I read Ann Leary’s contemporary fiction The Good House last winter (review) and was excited to read her new one and further intrigued to see it was a piece of historic fiction. In spite of being very different from that piece of contemporary fiction, this book lived up to it quite well with richly imagined settings, complex and flawed characters, and an honest depiction of alcohol.

The author discovered this aspect of history – the forced institutionalization of women deemed “feebleminded” in the 1920s for the express eugenics purpose of preventing them from having children – while researching her own family genealogy. (Please be aware that “feebleminded” is a pejorative in modern times. In the 1920s, it was a term used clinically to classify patients.) Her grandmother worked briefly as a secretary at such an institution. The author was made curious by the name of the institution and thus the research that led to this novel was borne. Read more about her perspective on the research process, connection to her family, and the history of this treatment of women.

One of my favorite aspects of Leary’s writing is the characters. She’s not afraid to let them be flawed. In this case, the flaws are partially a reflection of the flaws of the times and partially innate to the characters themselves. No one in this book is perfect, and yet you find yourself rooting for them anyway. It can be difficult from a modern perspective to understand why Mary’s initial reaction to the asylum is positive. Or why she doesn’t trust or believe Lillian right away. But this book does an eloquent job of showing why that is, for personal and societal reasons, and letting Mary grow and change on her own.

Another strength is in making the horrific problems clear without dwelling on them in a gratuitous way. By the end of the book, the reader knows exactly what’s wrong as the asylum, but it remained straight-forward and succinct about it. I dislike it when historical books about difficult issues have scenes that feel like they could have come from a Saw movie. This book avoids that well.

The book also highlights the very serious issues for interracial couples. But there is an interfaith couple for whom the same attention isn’t paid. It felt a bit pie in the sky to not directly address the issues facing a Jewish/Catholic couple in the 1920s. Especially when the Catholic half of the couple is serious enough about her faith that she attends weekly Mass and worries about when she can have Confession. This is a level of seriousness about her faith that made me question how she seemed to not worry at all about the issues facing her in an interfaith relationship. Given the attentive detail given to the interracial couple, it felt even more like a weakness.

I was interested as to how the author would handle alcohol in this 1920s historic piece given The Good House is largely about a woman struggling with alcoholism. Alcohol is not the focus of the book, but it is featured in ways that are realistic to the 1920s. In other words, while Prohibition is still in existence during the book, alcohol is pervasive in society. The downfalls of alcohol are well depicted, again, without being too gratuitous.

Overall, this is a well-researched and crafted piece of historic fiction that covers difficult ground with grace. Recommended to fans of historic fiction. But keep in mind the romance is a subplot in this one.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 336 pages – average but on the longer side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Book Review: Burn Baby Burn by Meg Medina

Summary:

Set in New York City during the tumultuous year of 1977, this focuses on Nora, a Cuban-American 17-year-old in her final months of high school and the summer immediately after. Son of Sam is terrorizing the city, shooting young people at what seems to be random, there’s a heat wave, and a black-out. Nora needs to figure out what she’s going to do with her life after high school, but her younger brother, Hector, is becoming more uncontrollable, and she needs to help her mother with the rent. All she wants to do is go to the disco with the cute guy from work, but is that even safe with Son of Sam around?

Review:

I really enjoyed this one. The setting was great – all the fun of the 1970s with none of the exploitation or sexual violence often seen in the movies and books that came out of that era. That is not to say that there is no violence (domestic violence, drug abuse, drug paraphernalia, arson, homes threatened by fires, brief and not very descriptive animal abuse) are all present. But still, compared to the movies from that time period, the violence is minimal.

I also enjoyed that, while the events of 1977 definitely are present, there is no unrealistic connections between the main character and them. You know how sometimes a main character in a historic piece is written in as having done something pivotal or having some connection to a historic person. None of that here.

While I appreciated the presence of Stiller (a Black woman progressive downstairs neighbor), I would have liked any indication of the queer culture that was present in NYC, especially with some particularly interesting moments also occurring in the 1970s (like the start of Gaysweek or the NY ruling on trans* rights). Given how many characters are heavily involved in the women’s movement, it seems like it would have been fairly simple to have a bit of crossover or touchstone between these.

Another thing that I think could have taken this book up a notch for those less familiar with disco would be a song suggestion for each chapter or a Spotify playlist to go along with it. Whenever music features heavily in a historic book, I think this is a good idea.

If you’re looking to dive into a quick-paced YA featuring disco and the reassurance that bananas years do pass, I recommend picking this one up.

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 310 pages – average but on the longer side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

Book Review: Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko

Summary:

Tayo, an Indigenous Laguna man, returns from being a prisoner of war of the Japanese in WWII without his cousin. Cousin is the technically accurate word, but since Tayo grew up in his cousin’s household after his mother left him there brother felt more accurate. Tayo is half-white and has always felt estranged, but this feeling is only heightened after the war. He is suffering from shell-shock and feels emptiness in the alcohol and violence the other veterans take solace in. When his grandmother sets him up with a ceremony with a shaman with unusual ways, things start to change.

Review:

He wanted to walk until he recognized himself again.

61% location

After years of reading many books about alcoholism – both its ravages and quitting it – I’ve started having to actively seek out the stories that are a bit less well-known. Now, this book is well-known in Indigenous lit circles, but I’ve only rarely heard it mentioned in quit lit circles. I was immediately intrigued both due to its Indigenous perspective (this is own voices by an Indigenous female author) and due to its age (first published in 1986). Told non-linearly and without chapters, this book was a challenge to me, but by the end I was swept into its storytelling methods and unquestionably moved.

He was not crazy; he had never been crazy. He had only seen and heard the world as it always was: no boundaries, only transitions through all distances and time.

95% location

This book is so beautiful in ways that are difficult to describe. Its perspective on why things are broken and how one man can potentially be healed (and maybe all of us can be healed if we just listen) was so meaningful to me. I’m glad I stepped out of my comfort zone to read it.

We all have been waiting for help a long time. But it never has been easy. The people must do it. You must do it.

51% location

I really enjoyed how clear this book makes it that any care for addiction delivered needs to be culturally competent to truly serve the person who needs help. It also does not shy away from the very specific pain of being an Indigenous person in the US, and how addiction both seeks to quell that pain and rebel against the oppressive society.

It’s rare for me to re-read a book, but I anticipate this being a book I re-read over the course of time. I expect each reading will reveal new things. For those who already know they enjoy this type of storytelling, I encourage you to pick this up. Its perspective on WWII’s impact on Indigenous peoples and alcoholism is wonderful. For those who don’t usually read this type of story, I encourage you to try out something new. Make the decision to just embrace this way of telling a story and dive right into it. Especially if you usually read quit lit or post-WWII fiction.

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 270 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

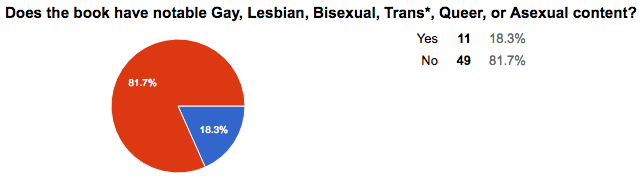

2017’s Accepted Review Copies!

Here on Opinions of a Wolf, I accept submissions of review copies via a form between February and December. The books I accept will then be reviewed the following year. So, the books accepted for review here in 2017 were submitted in 2016. You can view more about my review process here. You may view the accepted review copies post for 2014, 2015, and 2016 by clicking on the years. I view the submissions I receive as my own mini-bookstore of indie books. I browse the shelves and pick up however many spark my interest.

This year there were 60 submissions, and I accepted 2 books. This means books featured on this post only had a 3% chance of being accepted.

I actively pursue submissions from women and GLBTQA authors, as well as books with GLBTQA content.

Before getting to the accepted books, I like to show the demographics of books submitted to me. This helps those submitting this year for review in 2018 see what I had an overload of and where they might stand a better chance of getting accepted. It also allows for a lot of transparency of my review acceptance process.

Although there are still fewer women authors submitting to me than men, the proportion of women is up from last year’s 38.7%. I would really like it if this could hit at least 50/50 next year. Of the two books I accepted, one is by a woman author.

This went way down from last year’s 24.2%. I would very much appreciate any help getting the word out to LGBTQA authors that I’m actively seeking their submissions. Of the two books I accepted, one is by a GLBTQA author.

This also went down from last year’s 29%. One of my top three genres of books read last year was GLBTQA lit, so I obviously would hope for more of this in the future. Also of note: both of my accepted books have GLBTQA content.

The top three most frequently submitted genres were:

1) Fantasy (including urban) 31.7%

2) Horror 30%

3) Scifi 28.3%

Note that books fitting into multiple genres had all genres checked off on their submission. I actually didn’t accept any scifi or fantasy books so remember when submitting that the most frequently submitted genre doesn’t necessarily correlate to most likely to get accepted.

The review copies are listed below in alphabetical order by title. Summaries are pulled from GoodReads or Amazon. Both books will feature giveaways thanks to the author at the time of review. These books will be read and reviewed here in 2017, although what order they are read in is entirely up to my whim at the moment.

The Eighth Day Brotherhood

By: Alice M. Phillips

Genre: Historical Fiction, Horror, Mystery

Notable GLBTQA Content

Summary:

In Paris, 1888, the city prepares for the Exposition Universelle and the new Eiffel Tower swiftly rises on the bank of the Seine. One August morning, the sunrise reveals the embellished corpse of a young man suspended between the columns of the PanthEon, resembling a grotesque Icarus and marking the first in a macabre series of murders linked to Paris monuments. In the Latin Quarter, occult scholar Remy Sauvage is informed of his lover’s gruesome death and embarks upon his own investigation to avenge him by apprehending the cult known as the Eighth Day Brotherhood. At a nearby sanitarium, aspiring artist Claude Fournel becomes enamored with a mesmerist’s beautiful patient, Irish immigrant Margaret Finnegan. Resolved to steal her away from the asylum and obtain her for his muse, Claude only finds them both entwined in the Brotherhood’s apocalyptic plot combining magic, mythology, and murder.

Why I Accepted It:

It struck me as a queered up historical version of The DaVinci Code, and what’s not to like about that? Plus the excerpt was well-written.

Peacefully, In Her Sleep

By: Milo Bell

Genre: Mystery

Notable GLBTQA Content

Summary:

June Godfrey is a widowed crime writer living a well-ordered life in Barling, a village in Sussex, England. An anonymous letter, received by June’s friend Angela, reveals that the peacefulness of the quiet community may be illusory.

The letter’s author alleges that Angela’s aunt, Jacqueline Sims, was murdered. June is doubtful, yet when she begins a tentative investigation into the letter’s origins, she discovers that Jackie Sims was no sweet old lady. Jackie had been an unscrupulous blackmailer, and many could have wished her dead.

June uncovers startling secrets, and becomes entangled in the disappearance of an enigmatic teenaged girl. She crosses paths with the kindly, gentle Detective Inspector Guy Taverner, and when they join forces, they uncover a staggering and unexpected truth.

Why I Accepted It:

What struck me first was how well-written the excerpt was. When I saw that it’s a mystery set in an English village and had notable GLBTQA content, well, I had to read it.

Congratulations again to the accepted authors for 2017!

Interested in submitting for 2018? Find out how here.

Book Review: Fever by Mary Beth Keane (Audiobook narrated by Candace Thaxton)

Summary:

Summary:

Have you ever heard of Typhoid Mary? The Irish-American cook in the early 1900s who was lambasted for spreading typhoid through her cooking. What many don’t know is that she was an asymptomatic carrier. This was the early ages of germ theory, and most didn’t realize you could pass on an illness without any symptoms. Captured and held against her will on North Brother Island, it’s easy to empathize with her plight. Until she’s released and begins cooking again.

Review:

I grew up hearing the cautionary tale of Typhoid Mary, who was mostly mentioned within hearing range in combination with an admonition to wash your hands. But some people (mainly other children) told tales of her purposefully infecting those she served. These sentences were spoken with a combination of fear and awe. On the one hand, how understandable at a time when worker’s rights were nearly completely absent and to be both a woman and Irish in America was not a good combination. On the other hand, how evil to poison people with such a heinous illness in their food. In any case, when this fictionalized account of Mary Mallon came up, I was immediately intrigued. Who was this woman anyway? It turns out, the mixture of awe and fear reflected in myself and other children was actually fairly accurate.

I’m going to speak first about the actual Mary Mallon and then about the writing of the book. If you’re looking for the perfect example of gray area and no easy answers mixed with unfair treatment based on gender and nation of origin, then hoo boy do you find one with Mary Mallon. The early 1900s was early germ theory, and honestly, when you think about it, germ theory sounds nuts if you don’t grow up with it. You can carry invisible creatures on your skin and in your saliva that can make other people but not yourself sick. Remember, people didn’t grow up knowing about germs. It was an entirely new theory. The status quo was don’t cook while you’re sick, and hygiene was abysmally low…basically everywhere. It’s easy to understand how Mary was accidentally spreading sickness and didn’t know it. It’s also easy to understand why she would have fought at being arrested (she did nothing malicious or wrong and was afraid of the police). Much as we may say now that she should have known enough to wash her hands frequently. Wellll, maybe not so much back then.

Public health officials said that they tried to reason with Mary, and she refused to stop cooking or believe that she was infecting others. This is why they quarantined her on North Brother Island. Some point to others (male, higher social status) who were found to be asymptomatic carriers who were not quarantined. True. But they also acknowledged the risk and agreed to stop doing whatever it was that was spreading the illness. Maybe Mary was more resistant because of the prejudice she was treated with from the beginning. Or maybe she really was too stubborn to be able to understand what a real risk she posed to others. Regardless, it is my opinion that no matter the extraneous social factors (being a laundress is more difficult than being a cook, people were overly harsh with her, etc…) Mary still knowingly cooked and infected people after she was released from North Brother Island. Yes, there were better ways public health officials could have handled the whole situation but that’s still an evil thing to do. So that’s the real story of Mary Mallon. Now, on to the fictional account (and here you’ll see why I bothered discussing the facts first).

At first Keane does a good job humanizing a person who has been extremely demonized in American pop culture. Time and effort is put into establishing Mary’s life and hopes. Effort is made into showing how she may not have noticed typhoid following her wherever she went. She emigrated from Ireland. She, to put it simply, saw a lot of shit. A lot of people got sick and died. That was just life. I also liked how the author showed the ways in which Mallon was contrarian to what was expected of women. She didn’t marry. She was opinionated and sometimes accused of not dressing femininely enough. But, unfortunately, that’s where my appreciation fo the author’s handling of Mallon ends.

The author found it necessary to give Mallon a live-in boyfriend with alcoholism who gets almost as much page time as herself. In a book that should be about Mary, he gets entirely too much time, and that hurts the plot. (There is seriously a whole section about him going to Minnesota that is entirely pointless). A lot of Mary’s decisions are blamed on this boyfriend. While I get it that shitty relationships can cause you to make shitty decisions, at a certain point accountability comes into play. No one held a gun to Mary’s head and made her cook or made her date this man (I couldn’t find any records to support this whole boyfriend with alcoholism, btw).

On a similar note, a lot of effort is made into blaming literally everyone but Mary for the situation. It’s society’s fault. It’s culture’s fault. It’s Dr. Soper’s fault. They should have rehabbed her with a new job that was more comparable to cooking than being a laundress. They should have had more empathy. Blah blah blah. Yes. In a perfect world they would have realized how backbreaking being a laundress is and trained her in something else. But, my god, in the early 1900s they released her and found her a job in another career field. That’s a lot for that time period! This is the early days of public health. The fact that anyone even considered finding her a new career is kind of amazing. And while I value and understand the impact society and culture and others have on the individual’s ability to make good and moral decisions, I still believe ultimately the individual is morally responsible. And at some point, Mary, with all of her knowledge of the fact that if she cooked there was a high probability someone would die, decided to go and cook anyway. And she didn’t cook just anywhere. She cooked at a maternity ward in a hospital. So the fact that the book spends a lot of time trying to remove all personal culpability from Mary bothered me a lot.

I’m still glad I read the book, but I sort of wish I’d just read the interesting articles and watched the PBS special about her instead. It would have taken less time and been just as factual.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

Source: Audible

3 out of 5 stars

Length: 336 pages – average but on the longer side

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

Book Review: A Spell of Winter by Helen Dunmore

Summary:

Summary:

Cathy and her brother Rob live with their emotionally distant grandfather on family land in England because her mother left, and her father died in a mental institution. Cathy and Rob seek refuge with each other against the world, but World War I won’t let them keep the world at bay forever.

Review:

I generally enjoy controversial books, and I heard that this historical fiction included the always controversial plot point of incest. The short version of my review is: it’s amazing how boring a book about incest and WWI can actually be. For the longer version, read on.

The book is told non-linearly in what appears to be an attempt to build suspense. The constant jumping with very few reveals for quite some time, though, just led to my own frustration.

I was similarly frustrated by the fact that Cathy’s childish interpretation of her father’s mental illness never progresses. She never moves from a child’s understanding to an adult’s understanding. This lack of progress gave a similar stagnant feeling to the book.

Of course, what the book is best-known for is the incest between Cathy and Rob. I found the scenes of incest neither shocking nor eliciting of any emotion. There are scenes where Cathy and Rob discuss how “unfair” it is that they cannot have children and society will judge them. But then again there are scenes that imply that Rob took advantage of Cathy. Well, which is it? It’s not that I demand no gray areas, but the existence of gray areas in such a topic would best be supported by a main character with insight. Cathy remains childlike throughout the book. Indeed, I think the characterization of Cathy is what holds the whole book back. Because the book is Cathy’s perspective, this lack in her characterization impacts the whole thing. What could be either a horrifying or a thought-provoking book instead ends up being simply meh. A lot of time is spent saying essentially nothing.

That said, I did enjoy how the author elicits the setting. I truly felt as if I was there in that cold and often starving rural England. I felt as if I could feel the cold in my bones. That beauty of setting is something that many writers struggle with.

Overall, this book read as gray and dull to me as the early 20th century English countryside it is set in. Readers with a vested interest in all varieties of WWI historic fiction and those who enjoy a main character with a childlike inability to provide insight are the most likely to enjoy this book. Those looking for a shocking, horrifying, or thought-provoking read should look elsewhere.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, or using one of my referral/coupon codes. Thank you for your support!

3 out of 5 stars

Length: 320 pages – average but on the longer side

Source: PaperBackSwap

Counts For:

Bottom of TBR Pile Challenge