Book Review: The Dragon from Chicago: The Untold Story of an American Reporter in Nazi Germany by Pamela D. Toler

Discover the untold story of Sigrid Schultz, the fearless American journalist who exposed the rise of Nazi Germany—at a time when women were underrepresented in jouranlism.

Summary:

Schultz was the Chicago Tribune ‘s Berlin bureau chief and primary foreign correspondent for Central Europe from 1925 to January 1941, and one of the first reporters—male or female—to warn American readers of the growing dangers of Nazism.

Drawing on extensive archival research, Pamela D. Toler unearths the largely forgotten story of Schultz’s years spent courageously reporting the news from Berlin, from the revolts of 1919 through Nazi atrocities and air raids over Berlin in 1941. At a time when women reporters rarely wrote front page stories, Schultz pulled back the curtain on how the Nazis misreported the news to their own people, and how they attempted to control the foreign press through bribery and threats.

Review:

This wasn’t on my TBR or wishlist, but when I saw the cover and subtitle at the library, I had to pick it up. I love a troublemaking woman journalist trope—and this was that trope in real life, plus WWII! This nonfiction history book delivers, and in a reader-friendly way.

Despite its depth, this book reads almost as easily as fiction. The author takes care not to put words in the mouths of historical figures—every direct quote comes from letters, interviews, or official documents—yet the scenes are vivid and easy to follow. Each phase of Sigrid Schultz’s life gets just the right amount of attention, from her childhood in Chicago, to her teen years in Europe, to her time as a pioneering journalist. There’s even a well-developed chapter about her post-journalism years in Connecticut, which many historical biographies tend to gloss over.

When I review historical nonfiction, I like to share a few standout insights without giving away everything—so here’s what stuck with me the most.

Sigrid’s sense of identity was deeply American—despite living abroad from age 8 onward. She was so committed to her citizenship that she turned down a full-ride scholarship for singing because accepting it would have required her to renounce her U.S. citizenship.

Her personal life was shaped by loss. Sigrid lost her fiancé in WWI and her second great love to illness in the 1930s. It’s a stark reminder of how much death and grief defined the early 20th century. She didn’t choose to be an independent woman supporting herself and her mother—it was a necessity.

The 1916–1917 German food crisis led to absurd propaganda. Wartime shortages meant that Germans were forced to survive almost entirely on rutabagas. The government tried to spin it, dubbing them “Prussian Pineapples” and publishing recipes for rutabaga soups, casseroles, cakes, bread, coffee, and even beer (yes, rutabaga beer). (📖 page 17).

Although Sigrid’s reporting on the Nazis’ rise to power was the most gripping part of the book—especially during the 1936 Berlin Olympics, when the world was watching—what lingered with me was the story of her later years.

After WWII, Sigrid lost out on professional opportunities because she opposed the Allied occupation of Germany, believing that “any army of occupation is apt to be fascist in its tendencies”—regardless of the occupier’s intent. While I support people having strong ethical stances, her unwavering focus on this issue contributed to a series of choices that prevented her from adapting to the postwar world.

She struggled to transition from journalism to writing for magazines and books, finding it difficult to adjust her style. While the world moved on to focus on the Red Scare, she remained laser-focused on the rise of fascism, convinced it would resurface again. Her stubbornness and focus were, in many ways, her strengths—she even fought off eminent domain in Connecticut, keeping her home from being turned into a parking lot until her death. But they were also a hindrance. It’s real food for thought: when should we adapt, and when should we hold our ground? The balance between the two can shape an entire life.

The book primarily touches on diversity through Sigrid’s observations of the Jewish persecution during the rise of the Nazi regime. Unlike figures such as Corrie ten Boom or Oskar Schindler, she wasn’t someone routinely saving Jewish lives—but she did take small, meaningful actions when possible. One notable example: she convinced a friend to “buy” a Jewish man’s library, allowing him to falsely appear financially stable enough to get a green card—effectively saving his life.

She was also among the first reporters at the liberation of concentration camps and covered the Dachau war crimes trials. The book also explores the possibility that her mother was secretly Jewish, though it remains uncertain.

That said, the book is overwhelmingly told through a white woman’s lens, with little focus on wider global perspectives beyond Sigrid’s own.

Overall, this is an engaging, accessible read, written for popular audiences rather than academic historians. It offers fresh insights into WWII journalism, even for those already familiar with the era, and provides a fascinating look at a pioneering woman in media history. Recommended for readers interested in WWII, investigative journalism, and women’s history. For a more lighthearted take on trailblazing women in journalism, check out Eighty Days, the story of investigative journalist Nellie Bly’s race around the world.

If you found this review helpful, you might also enjoy my podcast, where I explore big ideas in books, storytelling, and craft. You can also support my work by tipping me on ko-fi, browsing my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral/coupon codes, or signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter. Thank you for supporting independent creators!

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 288 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Announcement: My New Podcast – Acutely Amanda: Fiction, Folklore, & Fiber Arts

I’ve always believed that stories aren’t only told through what we read with our eyes (or fingers, in the case of braille)—they’re also heard. But up until now, most of my content has focused on the visual. After months of writing, recording, and researching, I’m thrilled to share something new:

🎧 Acutely Amanda: Fiction, Folklore, & Fiber Arts officially launched today!

Whether you’ve been reading my blog for years or just found me while searching for a book review of Maybe in Another Life, this podcast brings together the threads of everything I love—fiction, folklore, and fiber arts.

What is Acutely Amanda?

Each season of the Acutely Amanda podcast has its own focus:

🌀 Odd-numbered seasons center on fiction and the writing life—featuring microfiction, drabbles, and flash fiction paired with behind-the-scenes insights and craft discussions.

🧶 Even-numbered seasons (coming soon!) shift gears into the world of making—crochet, sewing, needlework, and more—with fascinating facts about each craft and its history.

Season 1 includes 10 bite-sized episodes exploring themes like grief, queerness, housing, and aging—all wrapped in compelling short stories and thoughtful commentary.

If you’ve ever wished my blog had a podcast sidekick, this is it.

📅 New episodes drop every Tuesday at noon ET.

🎧 Where to Listen

- Watch on YouTube

- Listen on Spotify

- Apple Podcasts

- Sign up for my newsletter to get a sneak preview of Season 3 delivered to your inbox.

Why a Podcast?

Over the years, many of you have told me you love my stories and blog—but that audio works better for how you process and enjoy content. I wanted to make my storytelling more accessible, and podcasting felt like the natural next step.

As I worked on Season 1, I realized I wanted to give space to another passion—crafting. So I built a format that celebrates both:

✨ The real life behind the stories, and the stories behind the stitches.

And yes, the very first episode features a duck named Big Boye. 🦆

Support & Sneak Peeks

📬 Subscribe to the newsletter for sneak previews of future seasons

☕ Support me on Ko-fi to help keep the podcast going (and growing!)

Thank you for reading, listening, and stitching this journey together with me. I can’t wait to hear what you think. 💙

Book Review: Witchcraft for Wayward Girls by Grady Hendrix

A chilling blend of historical fiction and supernatural horror, this novel explores what happens when pregnant teenage girls—hidden away in a 1970s home for wayward girls—discover the dark power of witchcraft.

Summary:

They call them wayward girls. Loose girls. Girls who grew up too fast. And they’re sent to the Wellwood Home in St. Augustine, Florida, where unwed mothers are hidden by their families to have their babies in secret, give them up for adoption, and most important of all, to forget any of it ever happened.

Fifteen-year-old Fern arrives at the home in the sweltering summer of 1970, pregnant, terrified and alone. Under the watchful eye of the stern Miss Wellwood, she meets a dozen other girls in the same predicament. There’s Rose, a hippie who insists she’s going to find a way to keep her baby and escape to a commune. And Zinnia, a budding musician who knows she’s going to go home and marry her baby’s father. And Holly, a wisp of a girl, barely fourteen, mute and pregnant by no-one-knows-who.

Everything the girls eat, every moment of their waking day, and everything they’re allowed to talk about is strictly controlled by adults who claim they know what’s best for them. Then Fern meets a librarian who gives her an occult book about witchcraft, and power is in the hands of the girls for the first time in their lives. But power can destroy as easily as it creates, and it’s never given freely. There’s always a price to be paid…and it’s usually paid in blood.

Review:

I had previously read Grady Hendrix’s My Best Friend’s Exorcism and remembered liking it more than I actually did. When I revisited my review, I realized I had enjoyed the concept far more than the execution—and unfortunately, that’s exactly how I feel about this book as well.

One thing I didn’t realize before picking this up is that Hendrix is a male author. I read My Best Friend’s Exorcism digitally, so it wasn’t until I saw the author photo on my library copy that it became obvious. Now, that’s not to say men can’t or shouldn’t write about women’s issues—but in my experience, if a book is expressly about women’s experiences (such as pregnancy and abortion), I tend to dislike it when it’s written by a man. Hendrix acknowledges this in a note, explaining that his inspiration came from a family member’s experience as a wayward girl, and I appreciate the personal connection as well as the research he put in. That said, I still struggled with the execution. In retrospect, this also explains issues I had with My Best Friend’s Exorcism—especially the queer-baiting between the two best friends. The way their relationship was written didn’t quite reflect how best girlfriends interact. I now wonder if Hendrix was inserting subtext without realizing it. But I digress—back to this book.

This is a long book, and it takes quite a while before the supernatural horror elements appear. When they do, they feel sporadic—as if the book can’t quite decide whether it wants to be historical fiction or horror. According to the author’s note, an earlier version was pure historical fiction, and it shows. The witchcraft elements feel both tacked-on and underwhelming, lacking the impact they seem to be aiming for. The spellcasting scenes, in particular, drag on too long—the book repeatedly emphasizes how rituals are tedious, repetitive, and boring, and then actually makes the reader sit through them in full dialogue.

The novel also struggles with whether the witches are heroes or villains. At first, they seem to empower the girls in a feminist, girl-power way, but later, they’re positioned as the main threat. I can see the poetic logic in showing that these girls had no real options, but at the same time, a novel like this needs a stronger thematic core—a sense of hope, justice, or at least a clear vision for a better future. On the plus side, I never knew what would happen next or how it would wrap up. Even when I felt frustrated, I kept reading simply because I needed to know how it all ended.

While the book does include a Black teen girl at the home, the handling of race and racism felt superficial at best. The only acknowledgment of racism in 1970s Florida is a scene where the home’s director initially wants to separate the Black girl from the others, only for a hippie character to protest and swap rooms with her. That’s it. This felt wildly unrealistic for the time period.

Beyond this, there are three other Black characters: the cook, the maid (her sister), and a driver. While these are historically accurate roles, the cook is a blatant magical negro trope, complete with a sassy personality and a role that exists entirely to serve and clean up after the white girls. I cringed. A lot. The white characters take advantage of her kindness without any acknowledgment of how their actions impact her life. I also disliked how Black characters’ skin tones were described.

Readers should be aware that this book includes:

- Graphic descriptions of self-injury related to spellcasting.

- Traumatic childbirth.

- Forced institutionalization & adoption.

- Emotional abuse.

- Mentions of CSA & child abuse (off-page).

- A spellcasting scene with explicit Christian blasphemy. (Expected for witches, but I do think it could have achieved the same effect without spelling out the blasphemy.)

Ultimately, this is historical fiction with horror elements rather than a true horror novel. It would have benefited from stronger thematic direction and a more nuanced approach to diversity, avoiding the Magical Negro trope. The book understands that these wayward homes were a problem, but it doesn’t seem to take a stance on what should have been done differently. It sends mixed messages about abortion, single teen motherhood, and autonomy—leaving it feeling murky rather than impactful. Recommended for readers who enjoy historical fiction with a touch of horror—and who don’t mind waiting for the horror to arrive. For those interested in the real history behind these homes, The Girls Who Went Away is a must-read.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral/coupon codes, or signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter. Thank you for your support!

3 out of 5 stars

Length: 482 pages – chunkster

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Book Review: A Cyclist’s Guide to Crime and Croissants by Ann Claire

A charming cycling tour in the French countryside takes a deadly turn in this cozy mystery, perfect for fans of Emily in Paris—if Emily spoke French and solved murders between croissant breaks.

Summary:

Nine months ago, Sadie Greene shocked friends and family by ditching her sensible office job in the Chicago suburbs and buying a sight-unseen French bicycling tour company, Oui Cycle. Now she’s living the unconventional life of her dreams in the gorgeous village of Sans-Souci-sur-Mer. Sans souci means carefree, but Sadie feels enough pressure to burst a tire when hometown friends arrive for a tour, including her former boss, Dom Appleton. Sadie is determined to show them the wonders of France and cycling—and to prove she made the right move.

She hopes her meticulously planned nine-day itinerary will win them over, with its stunning seascapes, delicious wine tastings, hilltop villages, and, of course, frequent stops for croissants. When Dom drags his heels on fun, Sadie vows he’ll enjoy if it kills her. That is, until Dom ends up dead. The tragedy was no accident. Someone went out of their way to bring a permanent end to Dom’s vacation.

As more crimes—and murder—roll in, suspicions hover over Oui Cycle. To save her dream business, help her friends, and bring justice, Sadie launches her own investigation. However, mysteries mount with every turn. On an uphill battle for clues, can Sadie come to terms with her painful past while spinning closer to the truth—or will a twisted killer put the brakes on her for good?

Review:

If you’re looking for escapist literature, this cozy mystery delivers. A delightful, trope-perfect entry in the genre, it checks all the essential boxes—a murder that happens off-page? Check. A love interest suspicious of the FMC? Check. A dream career and a picturesque setting? Triple check.

One of the challenges of cozy mysteries is giving the main character an aspirational life without making them unlikable. Sadie, however, is wonderfully relatable. Her backstory is both heartwarming and tragic, making her move to France feel earned rather than enviable. She originally planned to start a bicycle tour business someday with her best friend—until tragedy struck, and her friend was killed in a hit-and-run. This loss becomes the catalyst for Sadie’s life-changing decision, and she makes it happen through a mix of financial prudence (as a former accountant) and a seller who values passion over profit. It’s a compelling, well-crafted setup.

The week of the fateful tour, Sadie’s not-quite-family but family-like friends arrive from the U.S., ostensibly to take her tour—but really, to check up on her. This dynamic adds a layer of personal drama, making the tour more than just a random mix of clients (though there are those, including a sharp-eyed reviewer). The result? Plenty of tension before the mystery even begins.

The French countryside and cuisine are absolutely lovely to read about, and you don’t have to be a cycling enthusiast to enjoy the journey. That said, I personally loved the cycling details, from the Is an e-bike cheating? debate to the hardcore Tour de France trainees Sadie encounters along the way. (If you love cycling too, check out the Bikes in Space anthology I have a short story in.)

Unlike in some cozies, the first murder (yes, first) feels eerily realistic. While I enjoy a good poisoned pie moment, this crime—especially as a cyclist—felt alarmingly plausible, adding genuine weight to the investigation.

One thing I often struggle with in cozies is the detective as a love interest—I tend to find detectives off-putting. However, this one worked for me, largely because his investigative approach felt fresh and culturally distinct. It helped maintain the escapist feel rather than making it feel like a procedural.

Speaking of characters, despite the large cast, I never once lost track of who was who. Each character felt distinct without veering into caricature. That said, the diversity felt a bit Eurocentric—the most notable examples being a Ukrainian refugee and an ex-convict. While I enjoyed both characters, I would have liked to see a bit more variety in representation given the size of the cast.

Halfway through, I was convinced I had solved the mystery. I was wrong. And once the reveal came, I could see exactly where I had been misled—not in a frustrating way, but in a deeply satisfying one.

This is a fun, immersive cozy mystery with a likeable main character, a realistic first murder, and plenty of French countryside charm. Recommended for cozy mystery fans who love an escapist read with a side of cycling, crime, and croissants.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral/coupon codes, or signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter. Thank you for your support!

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 346 pages – average but on the longer side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

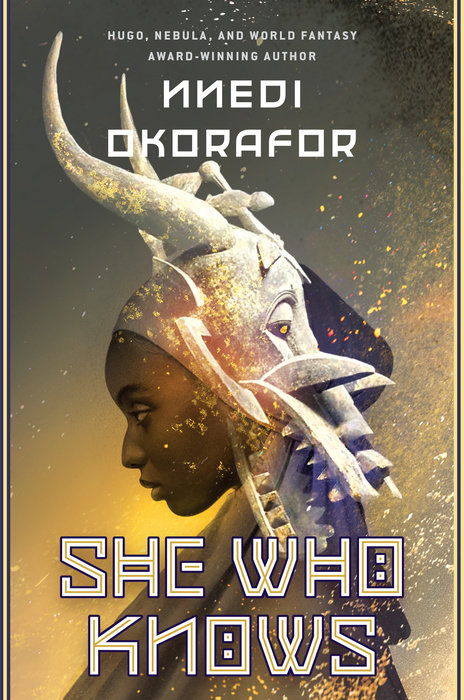

Book Review: She Who Knows by Nnedi Okorafor

Blending science fiction and fantasy in a near future West African setting, this engaging prequel offers a compelling plot blended with a unique coming-of-age story in a quick read.

Summary:

Najeeba knows.

She has had The Call. But how can a 13-year-old girl have the Call? Only men and boys experience the annual call to the Salt Roads. What’s just happened to Najeeba has never happened in the history of her village. But it’s not a terrible thing, just strange. So when she leaves with her father and brothers to mine salt at the Dead Lake, there’s neither fanfare nor protest. For Najeeba, it’s a dream come true: travel by camel, open skies, and a chance to see a spectacular place she’s only heard about. However, there must have been something to the rule, because Najeeba’s presence on the road changes everything and her family will never be the same.

Review:

This short, powerful book packs quite a punch with its quickly established setting, a main character you can easily root for, and action scenes that will leave you breathless.

This is a perfect example of science fantasy (also called space fantasy), blending elements of both science fiction and fantasy seamlessly. The science fiction aspect is revealed through its post-apocalyptic future—something happened to reset the world. Paper books are rare and kept in a community building, and the salt fields that Najeeba’s people harvest from were created by a drying up of the water. The fantasy elements feel just as integrated, from the “Call” that Najeeba’s people receive when it’s time to go to the salt, to the supernatural powers some individuals can access. (For another science fantasy read, check out my retelling of Thumbelina set on Venus.)

Though part of a prequel series to Nnedi Okorafor’s Who Fears Death, you don’t need to have read that to enjoy this one. I hadn’t read it either, and I never felt lost or like I was missing crucial context. The initial conflict—Najeeba’s desire to do something that’s typically only for boys—is easy to grasp, and the world-building is subtle and effective. By the time the more unique and fantastical elements come into play, I was fully immersed in the world.

Set in a future version of West Africa, this features Black protagonists, with other characters who are Arab. While some of the abilities that develop in the story could be read as an allegory for developing a disability, none are explicitly represented.

The plot kept me hooked, and while I was satisfied with the ending, I found myself eager to explore more of this world. I’m excited to pick up the next book in the series when it’s available.

Overall, this is a quick, engaging read that brings science fantasy to a West African future setting. It’s a refreshing take on the near-future genre, offering a new perspective that I look forward to exploring further.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral/coupon codes, or signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter. Thank you for your support!

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 161 pages – average but on the shorter side

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)

Book Review: The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World by Robin Wall Kimmerer

A Potawatomi author and botanist explores the concept of gift economies through the author’s reflections on nature, reciprocity, and the lessons of the serviceberry tree.

Summary:

As indigenous scientist and author of Braiding Sweetgrass Robin Wall Kimmerer harvests serviceberries alongside the birds, she considers the ethic of reciprocity that lies at the heart of the gift economy. How, she asks, can we learn from indigenous wisdom and the plant world to reimagine what we value most? Our economy is rooted in scarcity, competition, and the hoarding of resources, and we have surrendered our values to a system that actively harms what we love.

Meanwhile, the serviceberry’s relationship with the natural world is an embodiment of reciprocity, interconnectedness, and gratitude. The tree distributes its wealth—its abundance of sweet, juicy berries—to meet the needs of its natural community. And this distribution insures its own survival. As Kimmerer explains, “Serviceberries show us another model, one based upon reciprocity, where wealth comes from the quality of your relationships, not from the illusion of self-sufficiency.”

Review:

I was incredibly moved by Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, which beautifully wove together the spiritual and the scientific. So, I was excited to dive into her new book, The Serviceberry, which blends natural biology with economics—yes, you read that right.

This short book is gorgeously illustrated by John Burgoyne with thematic line drawings that complement Kimmerer’s reflections. The story centers on her harvesting serviceberries, and this simple activity becomes the starting point for a profound exploration of economic systems.

I’ll admit, before reading this book, I didn’t know much about serviceberries, even though I spent my childhood picking wild berries. After reading Kimmerer’s description and researching more, I’m still not sure I’ve encountered them in the wild myself. I wonder if having a personal connection to the plant would have deepened my connection to the book, much like it did with many of the plants discussed in Braiding Sweetgrass.

The core of the book discusses gift economies—systems of mutual support that thrive on sharing abundance. Kimmerer writes:

Gift economies arise from an understanding of earthly abundance and the gratitude it generates. A perception of abundance, based on the notion that there is enough if we share it, underlies economies of mutual support. (page 75)

Kimmerer uses her own harvest of serviceberries as a metaphor: after gathering more than enough berries, she shares them with her neighbors, who might then return the generosity by baking a pie to share. She connects this to examples like Little Free Libraries and free stands giving away zucchini, offering a hopeful vision of a world where wealth is measured not by money, but by the relationships we build.

However, I struggled to fully embrace this vision. While I appreciate Kimmerer’s focus on the power of sharing, I was reading this book during a time of travel frustration—waiting overnight for a massively delayed airplane—and found myself questioning the likelihood of these ideas. The concept of abundance feels hard to grasp when faced with the reality of scarcity—especially when airlines don’t have enough seats for stranded travelers.

I also hear the idealistic rebuttal: in a gift economy, I wouldn’t need to travel far to see family because we’d all be close by, sharing our abundance. But my personal experience with things like Little Free Libraries, where people dump books in condition too bad for anyone to use, makes me question the idealism of this system. While Serviceberry presents a beautiful vision of generosity, it doesn’t address the real challenges of maintaining such systems at scale.

Despite this, I still value Kimmerer’s generosity in donating all her advance payments to support land protection, restoration, and justice. Her actions speak louder than words, and that’s something I deeply respect.

Overall, this is a quick read that challenges readers to think about economics, abundance, and reciprocity in new ways. While it didn’t convince me of the feasibility of the gift economy, it certainly provided food for thought. I recommend it to those who are interested in reimagining our current economic systems through a natural lens.

If you found this review helpful, please consider tipping me on ko-fi, checking out my digital items available in my ko-fi shop, buying one of my publications, using one of my referral/coupon codes, or signing up for my free microfiction monthly newsletter. Thank you for your support!

4 out of 5 stars

Length: 128 pages – novella/short nonfiction

Source: Library

Buy It (Amazon or Bookshop.org)